What obstacles for game designers arise from the tension between gathering data from citizens and addressing a non-digital but spatially defined audience? This question arose during the Games for Cities game jam held on the 22nd and 23rd of march at the Designhuis in Eindhoven. A collaboration between Games for Cities, Het Nieuwe Instituut through the DATAstudio, the Municipality of Eindhoven, and the Design Academy of Eindhoven offered three groups of design specialists, inhabitants, researchers, and others that would take on a design challenge offered by the municipality.

In the north of Eindhoven is a neighborhood called Woensel Noord. Originally built in the 60s and 70s as a neighborhood to house mostly employees of the expanding Phillips business this neighborhood was shaped to accommodate car travel (to work) most of all. As time progressed Phillips and other companies moved, work patterns changed, and new inhabitants arrived and those living there grew older. The build-up of the neighborhood did not match the needs of its inhabitants anymore. Especially the boroughs Woenselse Heide and de Tempel are experiencing problems due to the older (and retiring) inhabitants feeling cut off from society, which is linked to rising levels of loneliness. The game designers were thus presented with a clear central problematic, spatial problems and a distinct audience.

The game design challenge became further complicated however. The loneliness is exacerbated due to the rapidly developing nature of the city of Eindhoven itself. Always the technical frontrunner, the city of Eindhoven has expressed a desire to become a smart city. While this can mean different things (Albino, Berardi, and Dangelico 2015), in the case of Eindhoven becoming a smart city means using sensors and registers to gather data about infrastructures and citizen actions or preferences to make the city more efficient, quicker, and democratic for its inhabitants. The gathering of data, in the shape of personal data, location patterns, and other statistical data is central here. However, in Woensel Noord the usual data gathering tools such as smartphones aren’t used that much by the inhabitants. As such, Woensel Noord is characterized as a ‘Data Desert’ – information about these inhabitants is hard to get. It is possible, but requires long and in depth interviews, something that goes against the efficient nature of smart cities. Next to this game designer Miguel Sicart expresses that “It is not enough to have access to [data] – access needs to be meaningful so that meaningful lives can be lived” (2016, 31). The game designers of the game jam were therefore tasked to standardize, streamline, humanize, and upscale the gathering of data in this neighborhood. To this end they were given a central problematic (loneliness), a spatial locale (Woensel Noord), a distinct audience (older adults) and a focus (data gathering). How can these elements be combined into games?

This report will chronicle the process, the arising obstacles and dilemmas, and a general reflection on the use of games in cities. In order to gain a better understanding of making games for cities that pursue a specific goal, the game jam is described and analyzed, introducing the following three insights:

- Designing for the audience requires reflection on of stereotypes and assumptions

- Thematic generalization creates tools rather than games for specific cities

- The approach to ‘the city’ is formative in the game focus, the data gathered, and the audience addressed

The many shapes of the designs are used as examples to gain further insight into games for cities. The first one of such insights can be found in the earlier mentioned focus on audience, as representative for the city.

An Elderly Audience?

Woenselse Heide and de Tempel house a relatively high percentage of elderly citizens – or more correctly named: older adults. 22% of the inhabitants of the area are over 65 years old (Eindhoven in Cijfers 2017). Usually these people have lived here all their life, having many of their needs provided for by their employer. Now, more and more changes occur as well as more newcomers arrive. About 20% of the inhabitants are newcomers such as immigrants (idem). These bring with them new practices and cultural habits, adding new dynamics to the neighborhood. Estranged from their familiar patterns, the older adults feel increasingly lonely, averaging about 7.5% of the inhabitants feeling somewhat to extremely lonely in 2011 and rising steadily (MSS 2011). How can game designers appeal to this group within this particular problem through a game? Simple right? Bring the people together and loneliness is over. We don’t need a whole paragraph to explain the importance of audience.

Wrong. We do. The link between older adults and loneliness is often understood simplistically, according to Eric Schoenmakers, gerontologist from the Fontys university of applied sciences. During the game jam it became clear that solving loneliness is not as simple as just increasing the amount of social contacts. An elderly inhabitant, Fons, functioned as a useful soundboard for assumptions about older adults. He expressed a desire for a few high quality contacts instead of a large network. To battle the level of loneliness is then not simplistically solved by facilitating social contacts but instead create meaningful interactions. But what is meaningful in this case? This brought the game designers back to the earlier identified adagio of city games: the players or citizens are formative in the process and their experience realm is central.

The loneliness then stems from feeling out of touch with society due to the many changes in daily life. Helping this feeling of loneliness go away then means giving them the feeling they can still participate and are valued in today’s society. This fuzzy goal can be concretized through the concept of “ownership,” defined by Michiel de Lange and Martijn de Waal as “the degree to which city dwellers feel a sense of responsibility for shared issues and are taking action on these matters” (2013). This can be qualified in a continuum. However, the dimensions of the degree of ownership was understood differently by each game designer team. Characterizing the shape of the ownership resulted in some different prototypes for each of the three design teams. Fundamental for these prototypes were assumptions of how older adults ‘function.’

One group for instance started out with the idea of an Intergenerational Tinder. The point of the game was to link younger people to older adults and then let each of them introduce them to an action ‘typical’ of the other demographic. Ideally, a granny would go clubbing with the teens. This prototype would provide the players with ownership by letting them and their activities be seen by others, acknowledged as still capable, and thus create better understanding among everyone.

Another group followed Fons’ (part of the design group) idea of higher quality contact. Not feeling part of society could be countered by showing that there are more inhabitants in the society that are like them. Relying on a shared reference frame and common memories or discussion points this group appealed to the older adults, measuring ownership by determining whether players feel more support in their own position. A high level of ownership means that that their isolation is not so destitute as once thought.

While following the earlier identified and theoretically discussed (Fullerton 2014, 3) idea of starting from the audience when approaching the central problematic– loneliness due to lack of agency – these early versions confronted the designers with their own assumptions about the audience. In the intergenerational Tinder for instance, what counted as typical actions of older adults was hard to predict without falling back into the familiar knitting, and playing bingo. The other prototype had to rely on imposed shared topics of conversation, also bordering on stereotypical, such as war memories. The assumptions shaped the mechanics of many of games, resulting in assumptions pervading the whole products. Without playtests the implied player, or “the role made for the player by the game, a set of expectations that the player must fulfill,” could not be in any way better defined (Aarseth 2007, 132). What happened here? In the Overvecht game jam arguing from the audience viewpoint created a game specifically suited for the area of Overvecht. What is different here?

There are two explanations. One is that in Overvecht the experience realm of the players was defined by their needs – jobs and communal security. In Woensel Noord the games have to be designed in such a way that the players – the older adults – like them in order to ensure meaning and thereby ownership. Identifying the tastes that will make a topic meaningful, or the preferences that go into ‘typical’ actions is more difficult than determining what someone desperately needs. Without playtests the players of Woensel Noord could thus not be properly defined.

The other explanation gave further depth to this tension in ownership. Instead of characterizing the neighborhood through its inhabitants, it can be argued that the game designers approached the spatial positioning through another approach: Data Gathering.

Data Focus

Thus it was not possible within this context to properly define the implied player and loneliness proved a more networked problem. Solving the individualistic problem of loneliness through a game was impossible as this problematic is mostly related to the surrounding personal network.The designers switched their attention to filling the data desert by charting the factors that disrupt personal networks and contribute to loneliness. Focusing on the games’ deliverables created three more focused games, but simultaneously lifted the games to a new non-spatial meta level – they lost their connection to Eindhoven and older adults – by creating games for a more general ‘neighborhood.’ To understand this change an overview of the final products is needed.

De 10.000

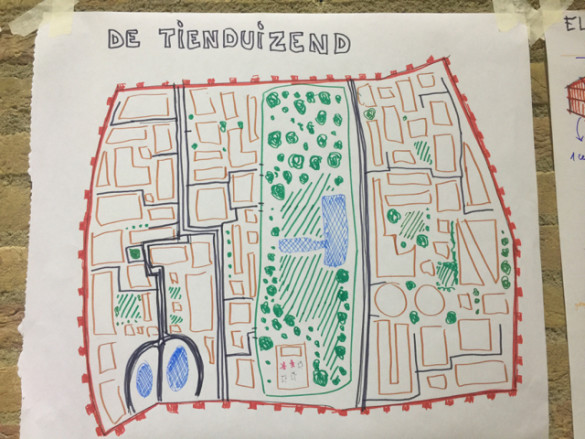

Named after the roughly 10.000 people that live in Woenselse Heide and de Tempel, this game strives to reveal the skills and identities of the inhabitants and facilitate real life interactions and initiatives. In a fictional scenario, overnight a wall appears around Woenselse Heide and de Tempel. The inhabitants are informed about when it will disappear and some necessary supplies are dropped in. But for the time being, no one leaves or enters. This offers the players the chance to form a new society needed to survive the period. This means that certain roles must be fulfilled, skills provided, and pressures withstood. Governed from a tent with a large game board depicting the neighborhood the players must create an inventory of the skills and resources available by placing color coded LEGOs on the appropriate location on the map, thus creating a visual overview of the neighborhood.

The game is played weekly, starting from the tent. Players enter and get a name badge. On this name badge are the skills they bring to the game, grouped into several general categories like safety or farming. Next to that each player lists the skills they would like to learn during the game. Based on their skills the players are given one of the more general roles in the game and can thereby pinpoint a coloured LEGO on the board on their house. Every week is focused around a theme – a resource or problem that must be sought out in the isolated enclave. The week on politics could for instance introduce the question of the kind of governmental system. These weeks invite the players to bring along, or locate people in the neighborhood that might have the required skills to deal with these issues and either make them play along, or learn from them. This way the game will ultimately foster face to face contact and ultimately involve more and more of the resources.

The solutions made to the dilemmas offered every week are chronicled in a special newspaper. This newspaper thus offers a community product to be proud of but also works as invitation to new players – you can leave your mark on the world. It also announces the theme of the next play session and any impending natural disasters. The newspaper is then a key interface as both a physical deliverable as a rabbit hole, facilitating insight and contact in the neighborhood.

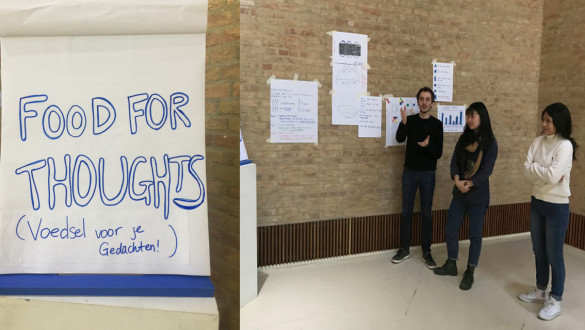

Food for Thoughts

This particular tool shows particular competence in getting players to play. An invitation for free food and showing off local cooking skills function as an excuse to play. During play inhabitants are connected to the relevant stakeholders who can gather their feedback about the neighborhood.

The game consists of three phases: invitation, eating, and playing. For the first phase six core players, (more motivated and recruited beforehand) will be sent into a local supermarket, with several tasks. Armed with a grocery list and some money, they must buy supplies for a dish. Simultaneously they must gather ten stories about the neighborhood, grouped around several topics, and invite five people to come with them to the community center for the dish and a more in depth exploration of their stories through a game. The supermarket setting makes it more likely to invite older adults due to the local community function.

The second phase takes place back at the community center. Here a volunteer cook and the core players prepare the recipe set out earlier. The invitees have the opportunity to add a recipe to the community cookbook that will inform the next sessions. Present as well is an expert of the topic of this session. Subsequently, everyone eats.

The third step evolves from the eating. The tablecloth is a map of the neighborhood with several key areas demarcated. On each plate are a differing statement and shape, such as “I feel safe here” or “Here is where I walk my dog.” The players have tokens in the shapes on the plates and in their personal color. They can now place the associated tokens on the places on the map where the statement applies to, creating an affective mapping of the neighborhood. Some places are often credited as safe, but some of the demarcated places are continuously deprived of these tokens. The local expert can take notes of the players’ explanations and inform how the places can be improved, creating a direct link between the players and the associated stakeholders. The numbers of tokens around each question are added to a score board. Each area is then scored, possibly creating a competitive element with players trying to appeal for the improvement of ‘their’ area.

Woensel Straks

This game builds on the earlier DATAstudio project of Roomsel Noord. This project drew attention to the possibility of house sharing in Woensel Noord. Many older adults live in large houses they’ve lived in with their family. With them moving out and the rents getting higher, some older adults can’t afford their houses anymore. Instead of evicting them, some rooms could be shared with entrepreneurs throughout the week. The shape of such a sharing economy however has to be made tangible and believable. Enter Woensel Straks.

Functioning as a platform with game elements this game is designed to talk about and test possible sharing scenarios. Making an imaginary scenario physical for all stakeholders can work wonders for the negotiations, and this game strives to do so through a set of toy-like models. There are three of these toys. One is shaped like a typical Woensel Noord house. However, the walls and rooms are moveable and can be restructured and filled with props to perform the scenarios. The other toys are models of the street and the direct neighborhood. These different toys then provide different scales which the sharing scenarios could influence.

The game is hosted by someone in the neighborhood, therefore already placed within a house, adding another tangible scale. Players select a sharing scenario to pitch to the others present (some of which might be the associated stakeholders). Each scenario needs a minimum of four players to go through to the next round: the pitch. Using the scale models the players visualize their ideas and do their best to communicate why and how it should be done. After a pitch, all the players vote on whether they like or dislike the scenario and they clarify their choice, giving the others a chance to try to remove the others’ doubts. This is where conflicts in expectations can be unearthed and the data deserts can be filled in – by conducting mini interviews. Ultimately, those scenarios that have gained most favor will be presented to the municipality or other executive parties. After four of these sessions a public event must show what has been achieved in the neighborhood. The game as of yet functions more as a platform instead of a game. Adding more forms of playful interactions could make this tool even more suited for local initiatives.

Thematic Generalization

These three games rely heavily on speculative design – a playing out of a certain scenario to which the formation is not decided beforehand. In a way by playing these games it is up to the players to decide how things could be. This form of design ensures a great degree of co-creation, satisfying a social and inclusive component (which is still important to battle loneliness, although not the only solution). This way the individualistic preferences and forms of ownership are inherently possible in each game, although not defined beforehand. While this is a successful way of tackling the problematic a striking realization occurred: games for cities turned into tools for issues.

The games are often setups for a certain phase of data gathering. In Food for Thought there is a playful invitation ceremony and ultimately some playful questions. In the 10.000 a narrativized diegesis gives way for an inventory of the neighborhood and in Woensel Straks a gamified voting mechanism facilitates a playful scenario roleplay. The task of gathering data is central and in this task gamification serves as a very useful means to structure this. Gamification refers to “collectively us[ing] … problem-solving skills not only to solve puzzles within a digital game but also to approach social and political issues in the real world” (Fuchs, Fizek, and Ruffino 2014, 9). The three games spice up certain daily actions, like going to the shopping mall, thinking about participating or getting to know other people, with simple game actions, such as discussing, voting, choosing and storytelling. In a way, the games themselves are more ways of gathering data through game techniques or invitations than fully fledged games – they have become tools.

This is not a bad thing. In many ways this shift has made the games very focused while still allowing for citizen additions. But this shift has paired with another one. The designers focused on gathering the data needed to resolve loneliness but did not specify loneliness anymore to older adults in Woensel Noord. They now generalized the theme of loneliness as inspiration for the game but not as its foundational goal. While the data will be useful to address the problem of loneliness, the link with Woensel Noord is severed through this shift.

The space specificity has vanished turning games for cities into tools for data. While some spatial aspects are considered – the supermarket as older adults meeting point in Food for Thoughts for instance – these games can be played anywhere, catering to a wider and more general context.

Still, the designers linked the games to the cities through several secondary products. One of them is the use of local scenarios in Woensel Straks for instance. These roleplays of these scenarios can be linked back immediately to the municipality, embedding this game firmly in the spatial location. The local newspaper of the 10.000 and the community cookbook provide a similar link to the local. As such, even though the games are not based on the specific audience profile of Woensel Noord, or its geographical build-up, these games manage to instill a feeling of ownership nonetheless.

What this shows is that games for cities can be approached from a more instrumental perspective as well. What goal these instruments pursue demands targeted design decisions which offer key cases to analyze in order to get a better understanding of the forms of city games.

Hammer meets Nail

The three designed games all have their own design specifics resulting in different strengths and applicability. This final section will look closer at how to ensure that despite generalization local elements can still inform game designs as well as what differentiating elements are most common.

When looking at how the shift from audience to data gathering the link with the location becomes secondary. Can we identify where this happens? The design considerations were conveniently outlined in a five step plan.

- Define the purpose of your game

- Characterize your players

- Specify the dynamics and interface of your game

- What datasets are required to play and design this game

- What are the desired outcomes

Since there are a multitude of ways to start a design the aptness of this method will not be discussed in its entirety (Van Boeijen, Daalhuizen, Zijlstra, Van der Schoor 2013). When solely focusing on using the games for data gathering in a specific context, a critical note can be made on the positioning on point 4 – the datasets.

In this sequence the datasets is only explicitly thought about after the game has already been largely designed. The datasets are a means to incorporate spatially specific aspects into a game, or at least implement the borders of the data deserts. By focusing on the game design first, which in this case is focused on the audience (as described before), the locale specific data is only used as flavoring – it colors the general design but is not specifically focused on it. This insight illustrates that part of the localization of an instrumental game has to happen in an early state. That way the local data can support degrees of ownership through the entire game.

So to create a more spatially specific game when designing a gamified data tool can be done by changing the design order. That way Sicart’s (2016, 31) call to “make the open data about us ours; … to see the patterns in the data, the structures that we help build” is more forcefully implemented, urging the game designers to closely analyze the data and implement it, instead of again solely working with the results. How have the games from this jam dealt with this localization? The 10.000, Food for Thoughts and Woensel Straks excel at creating a safe setting, player gathering, and forming imaginaries respectively.

The 10.000 does this through an analogy. The narrative of the Wall and its associated chronicle give the players more ownership of their neighborhood. They can literally make their mark on history. De Lange explains that urban games “ allow people to act on a wide range of specific urban issues through role-playing, building trust, forging collaborations and tapping into crowd creativity” (2015, 432). This is because play manages to create an open artificial setting in which experimentation is afforded and encouraged, transcending inhibitions. More so than the other two, the 10.000 relies on a fictional narrative to augment everyday life in Woensel Noord. As such it banks more on the experimentation of identity and role playing or learning for the audience itself. While not defining the audience particularly, the pursuit of data about skills in the neighborhood then yields a game that through narrative specifically spurs players to experiment.

Food for Thoughts alternatively focuses on audience gathering. The game itself is very simplistic – answer questions and place tokens. But the whole buildup attests of a very playful attitude. Sicart defines this as “a way of engaging with particular contexts and objects that is similar to play but respects the purposes and goals of that object or context” (2014, 21). Eating some dish becomes special due to the discovery of a question. Telling stories is turned playful by using colourful tokens to spice up the neighborhood or initially even being rewarded with food. The game turns data gathering through interviews into a playful affair, spicing up storytelling at all steps of the game. This game then cleverly plays with the threshold to start playing. While not necessarily linked to Woensel Noord, its design attests of a very strong rabbit hole character – it draws people in with a simple exchange.

Finally, Woensel Straks builds on visualizing imaginaries. Sicart calls mostly for the visualization of data in order to gain a better understanding of what it means and what can be done with it (2016, 31) and Woensel Straks builds on exactly this. By using playful models – toys if you will – players manage to make whatever can be imagined representable to all. Peter Peltzer from the Urban Future studio stresses that a shared visualization through “research by design” can make future scenarios be so much more convincing (Urban Futures Studios 2017). While virtually nothing more than a story telling tool, Woensel Straks’ toys allow the players to streamline negotiations by providing common reference frames. This gives players more control over their neighborhood and ownership of their future. While also building on experimenting Woensel Straks differs from the 10.000 in that it serves as a conversation facilitator instead of an identity experiment.

What these three different experiments show is that despite their generalized approach to cities through largely thematic data gathering methods, all three have their strengths and particular uses. Even though all games gather data, the specific problem of a neighborhood has to be identified to pinpoint the most useful game. This is another argument to analyze the datasets earlier in the process.

Conclusion and Reflection

The game jam for Woensel Noord showed some skipping and flipping of game design. While the audience was defined, designing from them on out proved problematic due to assumptions. The theme as well proved difficult to address due to the individualistic nature. Instead the main goal became data gathering in the more general sense that could in a secondary step be used to address loneliness. Tension between a known audience and a desire for data resulted in a shift to generalization. The games turned into tools that could be applied anywhere, but which due to their design could be used to provide different approaches to specific problems. What this game jam has shown is that it is possible for games for cities to be determined more by their outcome – in this case data gathering – than as a particular experience for a place. A city has many different dimensions. The job of game designers can then sometimes be to simply figure out what aspect games can facilitate in larger problem solving schemes.

About Games for Cities

City-Gaming holds great potential in addressing 21st century issues and the Games for Cities project, an initiative by PLAY THE CITY, has set out to build an integrated community, developing a common language, and supporting newcomers. THE MOBILE CITY and the Lectorate of Play & Civic Media at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences have partnered in this project in which researchers and designers explore the role of gaming for complex urban issues.

Games for Cities hosts three events in three cities throughout the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Utrecht), each dealing with a different urban issue (circularity, citizenship, inclusion respectively). In each city Games for Cities will organize a City game talk show to discuss the modeling of issues into games by actors involved, and a game jam to explore the design of city games. Games for Cities will be concluded with a conference and exhibition in Het Nieuwe Instituut on April 20-21 2016 in Rotterdam.

Sources

Aarseth, Espen. 2007. ‘I Fought the Law: Transgressive Play and the Implied Player’. In Proceedings of the 2007 DiGRA International Conference: Situated Play. Tokyo, September 2007.

Albino, Vito, Umberto Berardi, and Rosa Maria Dangelico. 2015. ‘Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives’. Journal of Urban Technology 22 (1): 3–21.

Boeijen, Annemiek van, Jaap Daalhuizen, Jelle Zijlstra, Roos van der Schoor. 2014. Delft Design Guide: Design Strategies and Methods. Revised Second Edition. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

Eindhoven. ‘Eindhoven in Cijfers’. Eindhoven Buurtmonitor. http://eindhoven.buurtmonitor.nl/jive/

Fuchs, Mathias, Sonia Fizek, and Paolo Ruffino, eds. 2014. Rethinking Gamification. Leuphana: Meson Press.

Fullerton, Tracy. 2014. Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Third Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Lange, Michiel de, and Martijn de Waal. 2013. ‘Owning the City: New Media and Citizen Engagement in Urban Design’. First Monday 18 (11). http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4954.

Maatschappelijke Steun Systemen. 2011. ‘ Demografische gegevens Eindhoven Woensel-Noord’. MSS. http://www.maatschappelijkesteunsystemen.nl/eindhoven/h/1662/0/5053/Eindhoven-Woensel-Noord/Demografische-gegevens-Eindhoven-Woensel-Noord

Peltzer, Peter. 2017. ‘Research by Design’. Urban Futures Studio. Universiteit Utrecht. https://www.uu.nl/en/research/urban-futures-studio/research-by-design

Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Playful Thinking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sicart, Miguel. 2016. ‘Play and the City’. In Playin’ the City: Artistic and Scientific Approaches to Playful Urban Arts, edited by Judith Ackermann, Andreas Rauscher, and Daniel Stein, 25–40. NAVIGATIONEN Zeitschrift Für Medien- Und Kulturwissenschaften. Siegen: Universität Siegen.