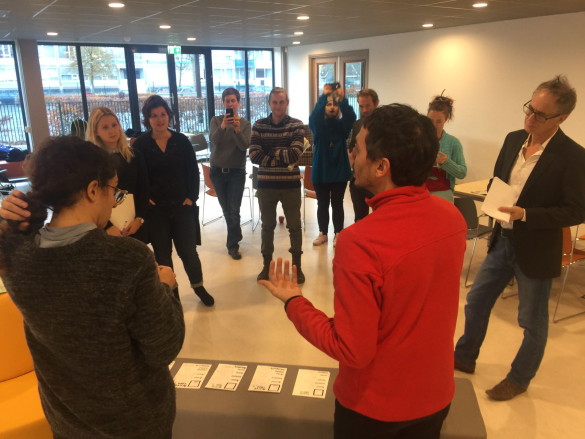

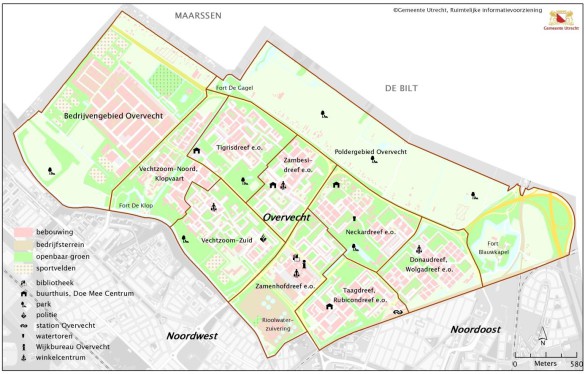

How do you design useful games for a neighborhood that houses about 170 different nationalities? This question shaped The Inclusive City Game Jam held on the 23rd and 24th of November 2016 in the Stadstuin Klopvaart in the Utrecht neighborhood of Overvecht. Briefed by the municipality of Utrecht, specifically the department in charge of Overvecht and its local initiatives, three teams of two game designers (Adam van Heerden & Genevieve Korte, Ekim Tan & Nina Hälker, and Gabriele Ferri & Txell Blanco Diaz) set out to design games uniquely fitted to the needs and strengths of the Utrecht neighborhood of Overvecht. Ultimately the three teams had two days to design something that would benefit Overvecht and could be deployed by the municipality as a useful, and self running, tool for citizens to use to their benefit.

This report will focus on this two-day process in which three design teams design games for a particular location – Utrecht Overvecht. Whereas in the previous Games for Cities workshop in Amsterdam the focus of the report was on the shared decisions made by the design teams the focus of this report will be on what decisions shape the localization in Overvecht of the designed games into the context of Overvecht? Localisation of urban games can be seen as their defining characteristic – it is what makes them urban for their location awareness is specifically addressed to cities (de Souza e Silva 2009, 407). The process of localization is however often taken for granted so insight into the decisions is needed. As this report discusses the game jam process several key considerations will be discussed. During the Utrecht game jam the following formative points for urban game design were discovered:

- Urban games are built partly from a network of social and physical materials

- Designing for locations requires addressing the local pragmatic experience

- Small differences in design can result in different uses

These insights will be discussed in this report while taking you through the formation of three games. The designer teams had to design games for Overvecht. They did not however enter completely blank. They were first familiarised with the dynamics of the neighborhood by members of the municipality.

Localised Problems and Possibilities

Members of the municipality and members of Play the City had created an inventory of possible initiatives.This gives an idea of what Overvecht is and what possibilities there are; it sets parameters on the “space of possibility” (Salen and Zimmerman 2003, 64), meaning the possible actions, meanings and relations.

One of the 10 neighborhoods of Utrecht, Overvecht was built after World War Two. It contains a lot of social housing apartments, sport facilities and nature areas. Due to this social and cheap housing and generally accessible facilities Overvecht welcomes a lot of newcomers every year. Many students, migrant workers, refugees, but also reintegrated delinquents flock to the many large apartment buildings of Overvecht due to its low prices. However, Overvecht also copes with unemployment, a higher percentage of residents with declining health, youth delinquency and criminality. Added to that, while many different nationalities and cultures live together, these negative characteristics, the isolated apartment condos, and drab buildings give Overvecht a negative and anti-social image, both in the rest of Utrecht as well as in Overvecht itself. This dynamism in inhabitants, as well as the abovementioned problems, can make it hard to feel at home in Overvecht. With a new stream of newcomers – refugees – coming to Overvecht, the municipality of Utrecht decided to cooperate with Games for Cities to address the experience and possibilities of coming to live in Overvecht.

The municipality did not come with a clear assignment or goal that had to be solved by use of a game. Instead the municipality asked for a tool they could deploy independently. The municipality wanted to know the mechanics for the following functional specifications:

- Replayable

- Rewarding for the inhabitants of Overvecht

- More rewarding with more replays

- Playable at different locations

The designer teams set out to design games that fit these characteristics and of which one of them or a combination would be a published game, to be launched in January 2017.

For this purpose the designers agreed that the purpose of the games should be to show what Overvecht can offer newcomers and what newcomers can offer Overvecht. The design team created an inventory of the available means and the current problems of Overvecht. For instance, Overvecht has the largest amount of nature out of all the districts of Utrecht and boasts about 170 different nationalities amongst its inhabitants. Simultaneously, Overvecht does not necessarily feel like home to many inhabitants, instead coming over as an affordable intermediary. Still, the Games for Cities team also gathered data on urban initiatives and actual number of skills available. To start their urban game design then, the team basically gathered ‘the materials with which to design.’

Taking a step back and analysing this process, at this point during the game jam a parallel with the earlier Amsterdam event can be identified. There the designers analysed the physical materials they had to work with first of all.This initial insight can be further worked out when looking at the Utrecht Game jam process. According to designers Youn-Kyung Lim, Erik Stolterman and Josh Tenenberg, “what determines the specifics of how to form [games] and what [they] should be composed or made out of is the materials” (2008, 14). Design guru Donald Norman also attributes the physical materials with shaping, signifying and constraining the possible action relations with the user (2013). What can be argued based on the earlier description is that in games for cities the materials obviously play a role, but that what ‘a city’ is made off is often less than physical. To effectively address urban issues through games then requires looking for the building blocks that make the city, which in Overvecht means things like crowded, isolated apartment buildings, sports, unemployment, cultural diversity, etc. A key insight that can be gathered from this first step of the game jam is that games for cities can be approached as networks of stakeholders, values, and actions.

Given this network perspective, different key values could be identified that merited gamification. Depending on the configuration of the network different games could be designed that strive to reinvigorate Overvecht in different ways. The design teams focused on the following three values.

- Sharing personal stories about the neighborhood

- Foregrounding the available resources (skills and demands) in Overvecht

- Increasing the meaning of the spaces available

From these preliminary identifications the games had to be formed. Starting from a network of various actors in a very open context the design themes now identified addressable problems in Overvecht. However, as would become clear during the game jam, and in the following paragraph, what makes an interesting game and what is useful for a neighborhood do not necessarily coincide.

Storytelling and Pragmatism

We’ve seen the road to the foundations, materials, and goals of the games and gathered a network perspective as building blocks from that. In the next step designers would set out to design the mechanics of the games. This section will reflect on the early exploration of mechanics in a contextualized game. More specifically, this section draw attention to the pitfalls that come with finding mechanics for a context and specifically addresses the question of necessity.

To make people love Overvecht the teams needed to know what meaning they attribute to their home. Within the network perspective, meanings and relations had to be unearthed, and the designers approached this through a design method with a heavy focus on storytelling – something like gamified interviews. The goal became to use stories to turn neutral space into meaningful place. Many authors, including Michel de Certeau (1984), Steve Harrison and Paul Dourish (1999), and David Harvey (2006), explain this distinction by stating that space is the opportunity while place is the understood reality. Space is the absolute physical space within which a lot can happen but which by itself does not have any particular singular meaning. De Certeau compares this absolute space to a top down view – you can see everything but you can’t do anything (1984). Places on the other hand are seen as personalized space – the actions and stories citizens can have attached to particular locales. The designers considered Overvecht to be too much of a space for its inhabitants – an empty physical locale with no personal appeal. The goals of the game became to instill a sense of place into space – to give it the meaning of home.

But what is a home? What feelings are linked to that? Home can be seen as the space of the house – the physical building – made meaningful for its inhabitants. A place to live becomes special when enriched with stories – memories – and when it becomes a hub for social and practical relations – like a place to house friends or the alternative to work. To make inhabitants feel at home in Overvecht then means appealing to this wider network through the game.

The game designers began to approach this side of Overvecht by focusing on revealing secrets through stories. This is a tested game design method, underlying successful games such as Mafia or Werewolf (Davidof 1986) and Diplomacy (Calhamer 1959). While the three games designed for Overvecht had a different shape, all of them focused on letting players tell stories. One game focused on letting players bring objects with a story with them. By telling the stories they could reveal a part of Overvecht to the others like they had not seen it before, by for instance telling about job opportunities or places that require a certain set of skills. Another one of the games revealed secrets in the way of the local and private economy. By letting inhabitants express their needs and skills through a passport, networks of skills could be mapped, showing that Overvecht has more to offer than it would seem. Finally, the last team focused on enabling face to face interaction, thus solidifying a social network gamified through the setting up of urban events. As can be judged from these game possibilities, all design teams focused on connecting people through personal stories somehow related to a gamification of the space – be it through local objects, the inhabitants, or events set in the space.

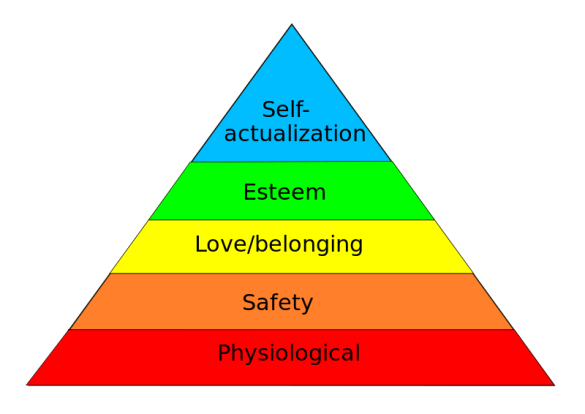

While the games seemed interesting, a reflection on the localization – the ultimate goal of this report – is necessary. Based on the meetings with the municipality, the goal of the game jam was to create a replayable game that inhabitants would undertake on their own. While storytelling games often yield interesting games, it is unlikely that this approach will result in feeling more at home in Overvecht. This hesitation can be explained by following Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs from his “A Theory of Human Motivation” (1943), which provides a means to understand human psychology (see figure below). The storytelling focus would cater to the third stratum of Love/Belonging. However, for many inhabitants in Overvecht the second stratum – Safety – in the form of job security, economic stability and its consequences are not always certain. To start telling stories when you don’t have a job yet or have to worry about getting food for a week goes against the primary motivations of the inhabitants. The insight that can be gained from this reflection is that interesting game designs in urban games may not fit the local desires, necessities or qualities of the local context.

The design teams concluded that their initial storytelling ideas ignored the specificities of the players in this specifically localized game setting. While the revealing secret approach could still prove useful, the core mechanic of storytelling had to be revised. This shows that when designing for games in urban settings, the players have to be identified on more levels than just the player experience. Instead the context of play becomes central. But how to design for that?

Networking the Skills and Needs

What do people in Overvecht really need? What secrets are still covered that should be enlightened to be of benefit to inhabitants and replayable? This section will explain the ultimate products and describe the lead-up to their formation.This description will give rise to an analysis on how different localization decisions can result in different values for a place.

With the new focus on the direct experience realm of the player, the focus was shifted from storytelling to gaining control of your life in the neighborhood – banking on the needs of the neighborhood instead of the wants. This control was linked to the idea of being able to solve problems – be it unemployment, feelings of insecurity, health, or services. The games relied on mechanics that match needs to citizen skills. This meant that basically all the games turned into skill based speed dates.

Central in these new iterations were two foundations which together grounded the games in their own personal urban context:

- The games relied on the experience realm of the players

- The games had a link to practical reality outside themselves

The games veered away from fuzzy territories of placemaking and meaning attribution. Instead the games embraced networking, self-presentation and concrete facilitation of cooperation. Games were now approached on their capacity to facilitate processes, like the search for jobs. Job hunt facilitations are already in abundance however. What can games add to this repertoire. When analysing the separate elements of the games it becomes clear that each game has its own form and with it their strengths. Looking closely at each games’ characteristics shows that inside each of them is an ideal functioning – the afforded actions fit the space of possibility. These games should then not be used outside of these parameters for that would over stretch their usefulness. It is within these different fits determined by different designs that the added values of games comes forward. Below is an outline of each game, every time ending in an analysis of the specific functions this game fits.

Aktiv-Echt – Gabriele Ferri & Txell Blanco Diaz

The game Aktiv-echt is designed to make players find solutions to personal problems using local resources. The game aims to stimulate residents into coming up with creative ways of tackling certain issues in their neighbourhood by realizing, offering, and deploying their skills. This could be an individual act, a collective protest, a social initiative or even the birth of an organization, giving actionable answers to complex social issues. Players submit problems they are struggling with, such as fearing walking home at night, and while playing the most relevant topics are chosen from these. At the beginning players make a skills and needs passport, chronicling their needs, such as walking accompanying, and skills, such as walking your dog at night, together with their contact information. The game is played by linking together skills and needs creatively to solve issues and rooted in personal life actions. The problem of walking home can be solved by walking together with someone walking the dog, etc. At the end of the game the contact information of those whose skills match someone’s needs is given so that actual action can be set up, but doesn’t have to be. The passports are collected and placed in a database to possibly help in future problems.

This game is easy to set up and lasts about 30 minutes, requiring about 4 to 6 players. It could be played in the elevators of the large apartment buildings of Overvecht, making it truly accessible to everyone, since these are the only really shared spaces in the buildings. The game facilitates, more so than provides, specific solutions by creating a database of social skill contacts that serves to connect the inhabitants in ways that are useful for their experience. Replaying is rewarded by basically offering a network event in which you get continuously more adequate and connected.

The fit of Akiv-Echt can be found in its format, goals, and mechanics. The format of the game is strikingly short and portable. More so than the other games, this game can be played in an elevator. The space of possibility this creates is very accessible which means that more players can be reached and thus ultimately a more detailed database is formed. Because of this format it is less likely to foster deep connections but even this is facilitated due to the exchange of info. The scenario discussions as goal keeps the game close to life collaboration and the discussion and networking mechanic build on this collaboration element. The game fits with making certain scenarios discussable and giving handles to start addressing them. The fit however ends there; the game facilitates out-of-game collaborations, it doesn’t provide solutions itself.

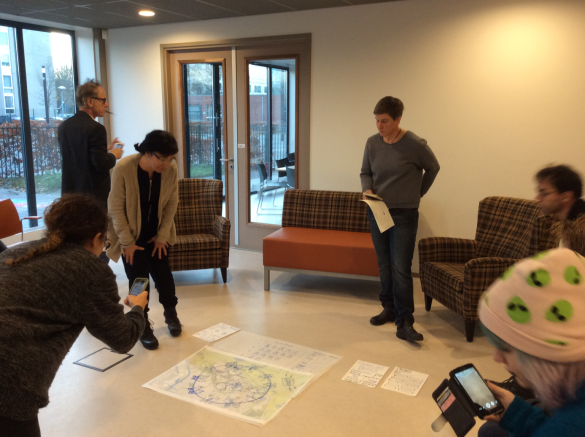

Discover Overvecht – Nina Hälker & Ekim Tan

The second game focused on giving players metaphorical control over their neighborhood as well as their own value for the community. Again armed with a skills and needs passport with contact data players now form teams of two. The teams act as mayors of districts of Overvecht and the individual players also play themselves as inhabitants of Overvecht characterized by their passports. The competitive goal of the game was to have the most successful and appealing district.

This success and appeal is to be gained by postulating the value of the district – identifying its needs, present skills (from the passports), and gather needed skills – and by selling your individual self as an asset to the district – in that you can use your skills to provide for the district. Proposing initiatives, attracting missing human resources and providing benefits in return will allow teams to make their district rise to the top. These scores carry over to the next session instilling a replayable competition. These mechanics allow the players to both learn to value their living environment, as well as identify its strengths and weaknesses and provide for them. Simultaneously, the players themselves will get confronted with their value in Overvecht in general. These mechanics enable this game to link to the experience realm of the players by explicitly relying on their individual values and the status of a district. It grants power on a metaphorical and literal level.

Next to that, an algorithm formed with the help of local initiatives, municipal employees and community members is used to determine what additions are deemed more valuable than others. This way the ruminations uttered by the players in their attempt to win the game session are also held against a metric that corresponds to daily life. As such, ideas, values, and skill used in the game can be just as useful outside of it.

This game fits different specifications than Aktiv-Echt. Here the mechanics provide a completely different space of possibility. The ability to role play as the mayor creates a meta possibility. The players can feel responsibility and value for their neighborhood. The same goes for yourself as player functioning as valuable resource. Selling yourself and your neighborhood becomes a procedural part of the game, allowing this game to let the players experiment with what they like about themselves and the neighborhood. It will thus rely more on reflection and performance than socialising and as such is more individualistic and reflective. Still, the algorithm gives this game a certain direction. Instead of just performing radical and funny roles the game fits with real world solutions, ensuring both self-exploration and neighborhood investment.

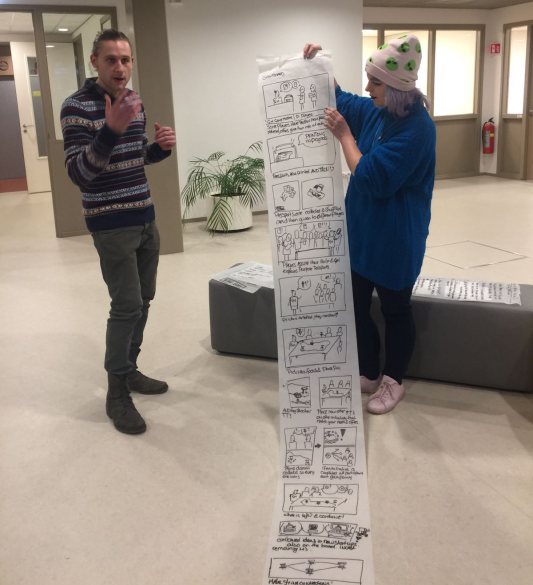

The Gain Board – Adam van Heerden & Genevieve Korte

The final game relied on an interesting switch. Players again made a skill passport but now these were collected and handed out anonymously and at random. The players then played as if they had the skills and needs of someone else, possibly coming up with new approaching the original owner did not consider. It could also boost self-esteem if a player imagines possible actions with the skills of their character which the original owner had long since waved away. Through this role-playing element this game further focuses on setting up initiatives and ensuring name-popularity and interest.

Players, having adopted a new role, play the game by positioning a player token next to a local initiative – already present or submitted – that fits their character and decide how to spend their time through time tokens. Each initiative needs ten tokens to take off. The game then requires bartering to get enough time investment for liked initiatives. This means interpreting and creatively deploying your skills or offers, which might redefine a character. At the end of the game the character passports are given back, possibly revealing surprising characterizations. Furthermore, each player token is connected with string to the initiatives they invest time in. This way players can leave with a physical image of how their skills and offers can be used throughout Overvecht. Offering facilitation of social initiatives, reflection on personal capacities, and generally discussing solutions to problems, this game had its real world effect in the revelations that could happen in a player.

The fit of this game is mostly determined by the role reversal and the playful character of the game. Instead of being driven by rules or heavy competition, this game works best with role play and experimentation – an inherent characteristic of play according to Miguel Sicart (2014). The game is mostly about exploration of boundaries. This higher amount of freedom makes this game more suited for the creation of deep social contact and the exploration of solutions. Instead of just networking, this game merits the exploration of the experience realm of others and safely present a solution – if it fails, it wasn’t you anyway.. The resource management as a grounding tactic contributes to this. The goal is to foster shared products, go out on a limb, try things. More so than the other games this game fits the exploration of new social contacts and solutions due to the safe veneer of role play.

Conclusion

All these games approach a game for Overvecht from a pragmatic point of view. To make a game for a specific locale then means to design for the needs of the players. This sometimes means relinquishing proven entertaining design methods and more blandly explore the network that forms the players’ lives.Depending on different design foci several strengths can be determined through a fit. While mostly facilitating existing processes, unique characteristics of games can specifically focus on singled out aspects such as networking, reflection, and socialising. What this shows about games for cities is that the experience realm can be identified in similar ways. However, how to link the game to reality – in what levels of abstraction, how co-created, and with what focus – can severely be altered through the use of different mechanics. This means that the next question to ask about games for cities will revolve around the specificity of the mechanic-function fit. How space or theme specific are games for cities? Where is the balance between a general tool and a localized game? The final event in Eindhoven offers a wonderful arena for this.

About Games for Cities

City-Gaming holds great potential in addressing 21st century issues and the Games for Cities project, an initiative by PLAY THE CITY, has set out to build an integrated community, developing a common language, and supporting newcomers. THE MOBILE CITY and the Lectorate of Play & Civic Media at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences have partnered in this project in which researchers and designers explore the role of gaming for complex urban issues.

Games for Cities hosts three events in three cities throughout the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Utrecht), each dealing with a different urban issue (circularity, citizenship, inclusion respectively). In each city Games for Cities will organize a City game talk show to discuss the modeling of issues into games by actors involved, and a game jam to explore the design of city games. Games for Cities will be concluded with a conference and exhibition in Het Nieuwe Instituut on April 20-21 2016 in Rotterdam.

Sources

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Harrison, Steve, and Paul Dourish. 1996. ‘Re-Place-Ing Space: The Roles of Space and Place in Collaborative Systems’. In Cooperating Communities: Proceedings of the ACM 1996 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, November 16 – 20, 1996, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, edited by Mark S. Ackermann, CSCW, and Association for Computing Machinery, 67–76. New York, NY: ACM.

Harvey, David. 2006. ‘Space as Keyword’. In David Harvey: A Critical Reader, edited by Noel Castree and Derek Gregory, 270–93. Antipode Book Series. Malden, MA ; Oxford: Blackwell Pub.

Lim, Youn-Kyung, Erik Stolterman, Josh Tenenberg. 2008. ‘The Anatomy of Prototypes: Prototypes as Filters, Prototypes as Manifestations of Design Ideas.’ ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction Vol. 15(2).

Maslow, A.H. 1943. “A theory of human motivation”. Psychological Review Vol. 50(4): 370–96.

Norman, Donald A. 2013. The Design of Everyday Things. Rev. and expanded ed. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. 2010. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Playful Thinking. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Souza e Silva, A. de. 2009. ‘Hybrid Reality and Location-Based Gaming: Redefining Mobility and Game Spaces in Urban Environments’. Simulation & Gaming 40 (3): 404–24.