A while ago I contributed an article about urban play and games and citizen engagement to the ECLECTIS final report “A contribution from cultural and creative actors to citizens’ empowerment”, on the invitation of Karien Vermeulen, Head of Programme Creative Learning Lab at Waag Society. ECLECTIS stands for “European Citizens’ Laboratory For Empowerment: Cities Shared”. It is a European cultural cooperation project “…gathering 11 European and international partners from 9 countries, working on citizens’ involvement in urban development, and sharing the same interest for developing creative projects inspired by artistic and inclusive approaches.”

A while ago I contributed an article about urban play and games and citizen engagement to the ECLECTIS final report “A contribution from cultural and creative actors to citizens’ empowerment”, on the invitation of Karien Vermeulen, Head of Programme Creative Learning Lab at Waag Society. ECLECTIS stands for “European Citizens’ Laboratory For Empowerment: Cities Shared”. It is a European cultural cooperation project “…gathering 11 European and international partners from 9 countries, working on citizens’ involvement in urban development, and sharing the same interest for developing creative projects inspired by artistic and inclusive approaches.”

The full report can be downloaded from http://www.dedale.info/_objets/medias/autres/eclectis-publication-965.pdf (18 MB).

Below the full article:

Playful Planning: Citizens Making The Smart And Social City

Dr. Michiel de Lange

Lecturer in new media Studies – Utrecht University, co-founder of The Mobile City

A changing “science of planning”

In the mid to late 19th century urban planning became a professional discipline in reaction to industrialization and the squalid living circumstances of a pauperized class. Urban design has since been concerned with realizing visions of ‘a better urban future’. However, in practice planning processes and outcomes often have been driven by fears and anxieties like overcrowding, congestion, sprawl, pollution, and – in current smart city policies – the suboptimal use of resources (see Andraos et al, 2009).21 As a result, planning has been accused of being undemocratic, reactionary and paternalistic. Urban theorist Peter Hall highlighted this fundamental tension between planners who want to impose a top- down totalitarian logic onto the populace, convinced that a better society is not designed by committee, and those departing from an on-the-ground perspective of people’s actual needs and desires (Hall, 1988).22

The same tension reappears today as digital media technologies profoundly alter urban life and culture. The technology-driven approach of many ‘smart city’ policies stands in stark contrast to citizen-centric and frequently playful ‘social city’ developments (de Lange & de Waal, 2012, 2013).23 This again affects urban design practices. Architects and planners like other disciplines are facing a declining legitimacy of expert knowledge, networked collective action fueled by media technologies, and shifts in the relationship between professional and amateur. Surely one can doubt that new media fuel a more egalitarian participatory society, the end of the expert, and the blossoming of high quality user content. There is little disagreement however that digital media profoundly alter professional practices that have long stayed aloof from them. In this contribution I look at how digital play and games affect the science of urban planning to become a ‘citizen science’ endeavor. First we see how play and games on different levels engage citizens. Then we see how play and games offer a fruitful perspective on citizen-driven urban design.

Urban play and citizen engagement

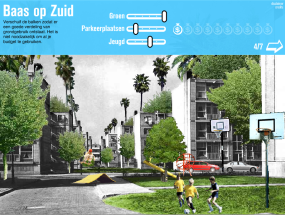

First, simulation games are used to engage people in planning processes. An early example is Baas op Zuid (2002)24 made by BBVH architects in collaboration with housing corporations. The online game was used for the redevelopment of two old Rotterdam districts. Players made design decisions for their neighbourhood: with a limited budget do I opt for more green, more parking spots or more playgrounds? Players immediately saw the consequences of their choices. Outcomes were aggregated and sent to the planners. Inhabitants thus acquired an understanding of stakeholder deliberations in complex trajectories. People who normally do not attend a town hall meeting now had a chance to speak up. Nonetheless in this case the professional remained the initiator and there was no profound shift in the relationship between expert and amateur.

Second, games are used to give people the potential to act on urban issues. An example is Community PlanIt (2011)25, where players answer questions and complete missions to earn virtual coins that they can pledge to real- world urban planning causes. Players also earn awards including bonus coins by participating in in-game deliberations. Through this game citizens, municipality and other stakeholders take up different yet equivalent roles and collectively try to solve problems. Through team cooperation these games build trust, which helps to overcome the tension between short and long term interests. Citizens now have become actual agenda-setters and problem-solvers.

Third, games are used to stimulate playful encounters with other people and places like in Koppelkiek (2009)26 by social game maker Kars Alfrink. Players in a neighborhood in Utrecht had to execute simple missions by taking a snapshot of oneself, for example together with someone else and a randomly found number. These pictures where publicly shown in the window of a neighbourhood center and acted as a conversation piece between neighbours. This game was explicitly created to promote playful interactions and serendipity. Players were invited to drop their usual defense mechanism and open themselves up. The game thus helped to cement social cohesion and trust.

Fourth, games are used to foster a ‘sense of place’, a feeling of belonging and care for the city. An example is the ‘subtlemob’ project As If It Were The Last Time (2009)27 by artist Duncan Speakman in which participants underwent a cinematographic experience in the streets of London. Participants downloaded an mp3 track and received a secret location and time to start the track on a portable audio player. They were divided into two teams. One team received instructions to perform a minimal scene, while the other group listened to a soundtrack and voice- over and became the audience of a filmic scene out performed out on the streets. This hardly qualifies as a game, yet it creates a shared playful experience and induces a sense of connectedness. Through a minimal intervention participants themselves turn the everyday into a magical situation. Playfulness here stimulates affective responses and emotional ties.

Playful citizen-centric urban design

In these examples we see that urban design is no longer the exclusive domain of architects and planners. Game makers, media artists, and app developers too are designers of today’s cities from the physical, to the social and the mental levels. Cities face ever more complex issues. This requires smart strategies to tap into the pool of citizen wisdom and participation. Games and play seem great ways to do so. However this requires planners to relinquish control, accept uncertain and ambiguous outcomes, and to allow possible failure. Games are composed of a set of constitutive rules, a material setting, and are actualized through the embodied activities of the players. This is comparable to what architects will recognize as program, design and use, but with a twist. Game designers create rules and settings yet the game is actualized by people actually playing. Players are not merely end users, they are active participants. They often engage in meta-play when they subvert the original rules, hack, cheat, exchange game tips, create derivatives, and tell stories about their own play. If we accept the idea of Dutch historian Johan Huizinga that play is not merely part of culture but that culture arises from play, then the variety of urban play and games experiments will eventually give rise to a new planning culture of the media city with a central role for citizens.

Baas op Zuid (2002)

notes:

21. Andraos, Amale, et al. 2009. 49 cities. Storefront for Art and Architecture, www.storefrontnews.org.

22. Hall, Peter. 1988. Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design in the twentieth century. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

23. de Lange, Michiel, and Martijn de Waal. 2012. Ownership in the hybrid city. Amsterdam. http://virtueelplatform.nl/g/content/download/virtueel-platform-ownership-in-the-hybrid-city-2012.pdf; de Lange, Michiel, and Martijn de Waal. 2013. Owning the city: New media and citizen engagement in urban design. First Monday, special issue “Media & the city” 18 (11).

24. www.baasopzuid.nl.

25. http://engagementgamelab.org/projects/community-planit.

26. www.koppelkiek.nl.

27. http://wearecircumstance.com/as-if-it-were-the-last-time.html.