The home page of the Social Cities of Tomorrow website opens with the following statement:

“Our everyday lives are increasingly shaped by digital media technologies, from smart cards and intelligent GPS systems to social media and smartphones. How can we use digital media technologies to make our cities more social, rather than just more hi-tech?”

Though smartphones, GPS systems and all manner of digital technology are the cutting edge technologies of our time, the struggles of urban organization and how to integrate technology into the living place are not new. The idea of the ‘city of the future’ has been around for a long time. Therefore, on this first day of the Social Cities of Tomorrow event, it seems appropriate to look back on the sometimes grandiose visions of generations passed.

In the late nineteenth century, Sir Ebenezer Howard published Garden Cities of Tomorrow. This book presented a model for a Utopian city. A city designed to let people live harmoniously with nature instead of in opposition to it. The garden city of tomorrow was to offer all the benefits of urban living, such as jobs and amusement, together with the advantages of the country life, being natural beauty, space and fresh air.

Howard’s work was Modernist in character in that it intended to provide a master plan – a total blue print for modern living. His future cities were to be designed from the ground up and required a blank slate. This is, of course, not always practical for a variety of reasons. Another example of a blank slate approach is Jacques Fresco’s Project Americana. Back in the 1950s and 60s Fresco envisioned massive circular cities filled with advanced cybernetic systems. Though he also emphasized the importance of social change, automated machine technology played an important role in the construction of these cities. Being cybernetic in nature, these autonomous machines were to automate all of the city’s operations, thus freeing the citizens from such menial tasks.

Another radical example is Peter Cook’s Plug-In City. As a member of the 60s avant-garde architectural group Archigram, Cook advocated a break with the functionalism of Modernist architecture. His Plug-In City proposed a radical mega-structure consisting of nodes and cells that could accommodate any type of architectural component – from housing, to offices to supermarkets. The flexibility of this arrangement was to ensure that the city always reflected the needs and collective will of its inhabitants. Though Cook was opposed to Modernist functionalism and his modular approach is evidence of a preference for a bottom-up development, his reliance on a massive plug-in mega-structure still required a blank slate.

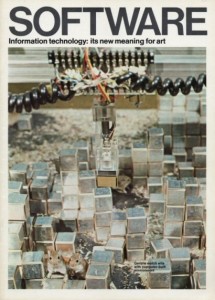

Seek is another, more playful, example of how technology might be used to revolutionize the concept of the city. Developed by Nicholas Negroponte with MIT’s Architecture Machine Group in 1970, Seek was an art exhibition that consisted of “a Plexiglass encased, computer-controlled environment full of small blocks and inhabited by gerbils.” Following pre-programmed instructions, a mechanical arm arranged blocks in specific patterns and attempted to correct any disruptions. The gerbils were, of course, the disruptors. The interesting part was that the arm also attempted to interpret the intentions of the gerbils and tried to place the blocks according to the gerbils’ objectives. As fascinating as this sounds, this, perhaps unsurprisingly, resulted in utter chaos with gerbil-sized Godzilla’s running amok amongst overturned blocks, strewn about like so many destroyed skyscrapers. This project makes a lot of assumptions about the intentions of gerbils and the ability to anticipate and program reactions to these intentions, however, it also speaks of a hypothetical architecture that automatically rearranges itself based on the wishes of its inhabitants. In this sense it is very similar to Peter Cook’s Plug-In City.

All these examples illustrate how different people form different times have conceptualized the use of technology as a means to revitalize urban organization and design. Of course, one always uses whatever technologies are available at the time. Whether that be cybernetics, automated construction facilities or something else entirely. Nowadays we look to social media, GPS systems and apps to make the difference. It is, however, important to remember that the primary goal of the city of tomorrow should be to facilitate better living. Easier, cleaner, happier. Thus, technology should be used as a facilitator, not as its own end. The Social Cities of Tomorrow workshops and conference aims to explore the possibilities provided by new technologies, yet the central issue remain: how can we create a living space that is comfortable for all its inhabitants? And just as importantly, how can we involve the inhabitants and all interested parties in this process? The Social Cities of Tomorrow workshops aim to answer these questions by contributing to real world cases. Today was day 1 of the event. Let’s see what the week brings us!