City-Gaming holds great potential in addressing 21st century issues and in the Games for Cities project researchers and designers explore the role of gaming for complex urban issues. The project consisted of three events in three cities throughout the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Utrecht), each dealing with a different urban issue (circularity, citizenship, inclusion respectively). In each city there was a talk show to discuss the modeling of issues into games by actors involved, and a game jam to explore the design of city games. With these experiences in city gaming charted, the Games for Cities project would conclude with The Games for Cities Conference, a two day event in Het Nieuwe Instituut on April 20-21 2016 in Rotterdam with keynotes, discussions, and games. Lots of games.

City-Gaming holds great potential in addressing 21st century issues and in the Games for Cities project researchers and designers explore the role of gaming for complex urban issues. The project consisted of three events in three cities throughout the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Utrecht), each dealing with a different urban issue (circularity, citizenship, inclusion respectively). In each city there was a talk show to discuss the modeling of issues into games by actors involved, and a game jam to explore the design of city games. With these experiences in city gaming charted, the Games for Cities project would conclude with The Games for Cities Conference, a two day event in Het Nieuwe Instituut on April 20-21 2016 in Rotterdam with keynotes, discussions, and games. Lots of games.

The central question of this conference was what the most important pitfalls in existing attitudes towards games used to address urban issues are and how should these be dealt with in the future? During the Games for Cities project several events were organized to explore and probe recurring design considerations and a common vocabulary when designing games for cities. Consisting of game jams and talk shows, these events brought together designers and stakeholders to identify assumptions and discover possibilities for games for cities in Amsterdam, Utrecht and Eindhoven. With the insights gathered from these meetings outlined elsewhere, the project required a final challenge: the corroboration. The gathered design insights, the games, the lessons, and the pitfalls would have to be confronted with the wisdom of bountiful experts and practitioners. As a final event a two-day conference was held at Het Nieuwe Instituut on the April 20th and 21st.

Organized by Play the City and partners in close collaboration with Het Nieuwe Instituut, this conference, hosted by Michiel de Lange, aimed at bringing Dutch city-gaming practices and international best practices into closer contact with one another. Four keynote speakers, Paolo Pedercini, Eric Gordon, Felix Madrazo, and Alfredo Brillembourg would reflect on certain key considerations of games for cities as well as central aspects of the urban uptake of such games. Several round table discussions with experts and practitioners would address the themes of circularity, inclusiveness and citizenship explored by Games for Cities and participants were invited to play a collection of games for cities during breakout sessions.

At the end of the conference Martijn de Waal summarised and reflected upon how the key notes, discussions and games foregrounded several general reflections that adequately chart, color, and delimit the playing field of games for cities. Paired with the insights gathered from the earlier events this report will set out to outline a general approach to games for cities. The key insights are as follows:

- Games for Cities are tools to facilitate involvement

- Conflict simulation in Games for Cities is an effective way to facilitate this involvement

- Transparent rules in Games for Cities help players understand how a city is desired to function

- Affording player input and discussion improves the level of reflection on these functions

- Games for Cities’ relation to space and the stability of the goal are formative in shaping the above capabilities.

These five insights when combined result in a general approach to games for cities. The insights reverberated through all of the keynotes so the order is irrelevant, although some authors placed more emphasis on specific points listed above. However, this report will chronicle each key speaker’s argument in chronological order while elaborating the points identified above. The arguments will be illustrated using the games from the breakout session or the earlier games for cities events (For a more general overview of the conference, see the Games for Cities website). Throughout the report findings from the earlier events will be tested against the presented arguments. So first comes a recap.

Recap and Inventory

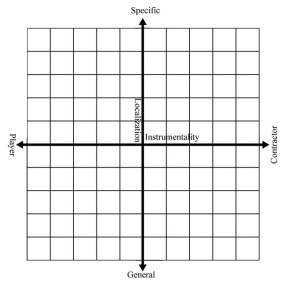

From the earlier jams and talk shows two variables influencing games for cities can be discerned. From Amsterdam and Eindhoven came the variable of spatial specificity, which should be seen as a continuum ranging from place specific to more general. Depending on where on the continuum the game falls, different design processes will take place, some relying more on the material reality while others appeal to a more general space. Utrecht introduced the variable of instrumentality locus which was further complicated in the Eindhoven event. This variable ranges from a focus on the audience experience to pure contractor instrumentality. Both of these variables are not essential to games for cities but do help in understanding the design process, the decisions taken, and their ultimate viability. This means games for cities do not follow a unilateral pattern, but instead can develop into many directions, focusing on different actors, and fitting to a plethora of different problems.

Given these two variables a more granular understanding of games for cities can already be discerned. In the graph four different approaches can already be imagined, all linked to different kind of strengths and pragmatic uses. These heuristics can help create a common lexicon for games for cities. To see the value of such additions they have to be held against reality. What does the field say about this? That is where the Games for Cities Conference comes in.

Given these two variables a more granular understanding of games for cities can already be discerned. In the graph four different approaches can already be imagined, all linked to different kind of strengths and pragmatic uses. These heuristics can help create a common lexicon for games for cities. To see the value of such additions they have to be held against reality. What does the field say about this? That is where the Games for Cities Conference comes in.

1 Paolo Pedercini (@MdeLange)

The Subtle System of Simcity – Paolo Pedercini

The first speaker of the conference was Paolo Pedercini, founder of the radical game company Molleindustria. Kicking off the conference Pedercini took the bull by the horns by addressing one of the most influential games for games for cities: Simcity. Adapted from a level editor in 1989 by Will Wright the simulation of a complex social system such as a city became the ruling paradigm for games featuring cities that still continues today, although in different formats (De Lange 2009). From IBM’s City One to Block’hood, games for cities often rely on a simulation that somehow models the complex social system that is the city. Pedercini however argues that despite the prevalence of this format, an uncritical uptake is more detrimental than beneficial.

Simcity won several prizes for its quality of simulation, even scoring ‘Best Educational Program’ in 1989. Given this focus on simulation and even education, there is a certain reliance on realism or verisimilitude in the functioning of the Simcity system. This is exactly what Pedercini revolts against. Simulating a complex system requires a degree of simplification; based on the mental model of the designer about how the system works. This means certain aspects of a system are left out while others receive emphasis. In the words of Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum, games contain “values,” by which they mean that “societies have common … values; that technologies, including digital games, embody ethical and political values; and that those who design digital games have the power to shape players’ engagement with these values” (2014, xii). Given that some actions in Simcity result in success while others result in chaos implies that a certain value system is at work here – one that claims to be and is regarded as realistic or educational. Basically what this means is that the designers have implicitly programmed the game to reward one type of city – in this case the North American neoliberal grid structure. Building a city on a mountain with high stratification and wealth distribution will lead to success in the game, while a cultural utopia will see your coffers dry and investors evicted.

Pedercini argued that aforementioned values in games – in this case the system values or system literacy – should be more explicit in games for cities. Once this “space of all possible actions that might take place in a game” (Salen and Zimmerman 2010, 69), or the space of possibility, becomes visible, players can start to explore other possibilities, breaking the rules and appropriating them (Sicart 2014). This will ultimately result in players being more involved with the actual city system than with just the game. Highlighting the values and rules of a system will then familiarize the players with the possibilities of urban involvement instead of just pushing them into a mold that won’t hold up against the more complex reality. That’s why Pedercini argued for more transparent rules in games for cities and more attention to their system literacy in order to give players more control over the available possibilities.

Holding Pedercini’s outcry against the earlier discussed variables of spatiality and instrumentality, Pedercini seems to express a preference for the more player focused side of instrumentality. To him games for cities should not aim for a specific purpose but facilitate meaningful play, which in this case means familiarizing the player with systems through which cities are conceptualized, in order to challenge them and come up with alternatives. While this is a common heard cry (Stenros and Wærn 2011; Sicart 2014, 2016; Gordon and Walter 2016a) Pedercini’s argument adds a new dimension to the spatiality variable: the value of spatiality. While a game may be playable at every location, the system of the city is can be more or less specific – such as Simcity’s Western Capitalist system. Where on the continuum a game falls ideologically should be made explicit so that it becomes clear what kind of city or involvement a game fits and how to challenge it. Pedercini as such introduces a value characteristic to the heuristics, building on giving the player insight. This trend was continued by the second speaker, Eric Gordon.

2 Eric Gordon (@Diegopajarito)

Meaningful Inefficiencies – Eric Gordon

From Pedercini’s talk came the call to contextualize the values that form the city system. Playing games for cities shouldn’t be a monolithic affair but should make the player more aware of the different positions. While agreeing on many fronts, the second keynote by Eric Gordon expanded on this with a more general critique on games for cities. Gordon, founder of the Engagement Lab and professor at Emerson College, stresses that games are autotelic – they are played for the sake of playing. Gordon followed the definition of game as presented by Bernard Suits in his book The Grasshopper:

To play a game is to attempt to achieve a specific state of affairs [prelusory goal], using only means permitted by rules [lusory means], where the rules prohibit use of more efficient in favour of less efficient means [constitutive rules], and where the rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity [lusory attitude] (1978, 54-55).

This autotelic nature echoes Pedercini’s idea that games with city systems should not be used to force players into thinking in line with a particular city system. Gordon would continue to generalize these points by diving into ‘meaningful inefficiencies.’

By relying on the autotelic nature of games, according to Suits’ definition, Gordon characterizes games as means of inefficiency. Playing golf is fun because getting the ball in the hole is challenging, not because its efficient. Because of this inherent drive to inefficiency (or failure (Juul 2013) or uncertainty (Costikyan 2013)) Gordon questions the value of games for cities. As was also claimed during the Amsterdam talk show, games can only work as facilitators, they should not be used as quick fixes for urban issues. Such a goal oriented tool instrumentality goes against the inefficient nature of games. Gordon even went as far to claim that to improve games for cities the main task was to not use games for cities.

Gordon curbed everyone’s enthusiasm but he continued to contextualize his claims. Less games should be taken with some salt – Gordon meant less games that see the player as a good user “where the citizen is instrumental …, as if citizenship were merely acts of production and consumption” (Gordon and Walter 2016b, 4). Here Gordon echoes Pedercini in that he urges games to not blindly force one normative value on the players. Instead, Gordon goes even further than Pedercini when he completely disregards the tool aspect of the instrumentality variable. For Gordon the main part of games for cities is their facilitation of citizen involvement by relying on meaningful inefficiencies.

As the main goal is to involve citizens in neighborhood actions games should function as invitations. Inefficiencies in games act as intrinsic motivations that allow players to discover new ways of overcoming the obstacles – it invites them to play. Gordon stresses the subversion possibilities, which make inefficiencies meaningful because players appropriate them in a personal, creative way (Sicart 2014). This appropriation results in a certain degree of co-creation, which was touted as important during several talk shows. This way the players get familiarized with involvement in a safe environment and the values of the city pursued become apparent and discussed (de Lange 2015). The focus on meaningful inefficiencies as invitations to involve players was a key theme that shaped many of the other talks of the conference. Setting the general tone of designs, Gordon stressed that players and their play are more formative for games for cities than the ultimate positioning in the city as it is only an invitation tool for the citizen. How this general directive would take shape in specific designs was elucidated by the third speaker, Felix Madrazo.

3 Ego City

Ego City and Conflict Simulators – Felix Madrazo

Having had a firm impression of the actual use of games for cities and a wake-up slap regarding their transparency, the sights were now set on concrete design advices, with question like ‘how do you make circularity fun?’ and ‘what was the experience you were going for?’ during the round table discussion. Who better than Felix Madrazo from the Why Factory to give an answer to these questions.

Cities struggle with (sub)urban sprawl wherein citizens move away from the center into mono-functional, car reliant suburbs, leaving the center decrepit and out of touch, often reliant on tourism. Madrazo and his team developed a game, Ego City, that would counter this suburbanization by charting what citizens actually want in a house, something they need to flee for to get. Instead, in Ego City, the main selling point was that players could actually follow their dreams, designing a house that would fit their wildest dreams. Want one big library? Design a shape and go ahead. A rollercoaster in your house? Plot the course and go crazy! Instead of worrying about the big picture of urban supply the Ego City game allows individualism to run rampant, thus providing for everyone’s desires. The players could role play their wildest dreams – such as The Big Lebowski’s Dude house containing a bowling alley and a carpet – which gives the game a playful character according to Roger Caillois’ early play categories (2001). By minding their own business and following what they want instead of what they should get new constellations get shaped and incorporated together.

Why is this game interesting in the wider perspective of games for cities? The next step after the design is to fit everyone’s dream house into a limited space. This is where Madrazo conceptualizes games as conflict simulators. By giving every player a personal stake – their dream house – in occupying a limited space, ultimately conflicts will arise. These conflicts go against the most efficient way of building (suburbanization) and instead become a meaningful inefficiency – the space where new possibilities of using space can arise in this case. Creating a no-holds-barred landgrab opportunity different uses of space are invented and accepted, as long as dreams can be realized. During development Madrazo explored different ways of conflict, and especially when it should appear. Players could just try and build their house and only conflict if a space was double booked, but another mode made players actively conquer territory and another was algorithmically decided. Each way of dealing with conflict resulted in different player relations, forms of urgency, and, as a result, space occupation. The effect of this conflict simulation was twofold:

- It added an agonistic element to the game. It also adds mimicry – or role-play – to the game. Such a conflict and role-play focus manages to make topics such as housing, circularity, and space management entertaining.

- Ego City became a metaphor or tool for thinking about housing questions and conflict resolving. As meaningful inefficiency the game urges players to pursue their dreams through new innovative ways, creating a safe exploration for actual urban conflicts.

What this means for games for cities is that games, through their entertaining inefficient moments, can simulate conflicts and therewith jump start player interaction and reflection outside the game.

With the spatiality of the game being generally ubiquitous, Madrazo conversely convincingly argues for a complete audience instrumentality in design instead of a tool perspective. While the game is a tool for thinking and facilitating, it totally stems from the purpose of giving the player the experience of living out their dreams. This focus on player experience places games for cities more in a game design perspective, following several design theories (Fullerton 2014, 3; Sicart 2014). Madrazo then takes a more playful or gameful approach to games for cities, starting from the player experience or the form as a game and then sees what can be done with it. This tempering of expectations is in line with Gordon’s warning but at the same time raises questions about whether games for cities can be instrumentally designed without handing over some of its game functions such as enjoyment.

This striking approach of Madrazo to games for cities can perhaps be linked to his conception of games as conflict simulators. In his game there is a certain degree of competition – whose house gets built to the best of their dream design? This contest element is often absent in games for cities, more often opting for a co-operative or at best a co-operative asynchronous contest wherein the players together must beat ‘the system’ and can often win based on individual goals (Fullerton 2014). Most games during the breakout sessions also required an often speculative design element wherein players together come up with scenarios that explain how the future could be managed. Madrazo showed that this was also possible in fierce competition and that the game characteristics of games for cities should not be ignored in favor of a better simulation of the process, as this is, as Pedercini noted, just one possibility to explore.

4 Alfredo Brillembourg (left) (@Diegopajarito)

Games as a Census – Alfredo Brillembourg

The opposite possibility to the trend sketched by Madrazo was offered by the fourth and final keynote, Alfredo Brillembourg, artist, professor at the university of Zurich, and founder of the Urban Think Tank. Through several iterations of a game Brillembourg and his team designed a game that was very spatially specific and ultimately was more focused on a tool like use, although still useful to the players. The games his team designed have been deployed in Venezuela, South Africa, and Switzerland, exploring the possibilities of non-standardized urban densification.

Like Madrazo, Brillembourg argued that games are useful technologies to instigate conflict. Change can only be achieved through conflict which is the essence of games, according to Brillembourg. Instead of relying on games to make complicated topics such as suburbanization more enjoyable like Madrazo, Brillembourg uses games to improve the process of participatory planning. He does this by focusing the game on the process of building itself, combining bottom up processing with top down planning.

The four iterations of the game can be characterized as cooperative communication facilitators that process information about how and where to build, often with a physical model. The goal was to play with city blocks and organizing them better by building on top of other houses and more geometrically. The mechanics of the game basically revolve around resource management – what elements are in the buildings that have to be relocated and what space is available, as well as what emotional requirements need to be met. The different planning possibilities are then made and discussed by the inhabitants and the stakeholders, ultimately reaching a contract with the community that is liked by everyone.

This is where the game differs mostly from Madrazo’s approach: it is basically a tool to create a census of everyone’s preferences. Instead of providing a player experience, the game loses its ‘gameness’ and facilitates a more complex and complete form of data gathering. Data by itself is not enough because they have to be complemented with ideas from the ground up. This is what makes this game a useful communication facilitator: it creates an organized discussion with rules adaptable from the ground up. This idea of adaptable rules was already introduced by Linda Hughes in 1983 where she observed that many games have a set of unwritten but very formative rules (1983). Other than Pedercini’s coded city system these rules are often not coded and basically refer to ‘good practice’ that makes interaction happen frictionless. Brillembourg’s game manages to bring out or at least build on these rules in the process of urban planning and densification. Following this more flexible set up the players together form a scenario that is held against ‘the system’ – a series of metrics that measure liveability. By cooperating – which in this case actually means data gathering in a more complete way – the players can try to beat the system by providing a better living situation for themselves. Solely a facilitator, these scenarios can now be submitted to the official urban planning channels – which opens up a whole new battleground, where other games might help with (such as Redesire).

Brillembourg’s approach to urban games is highly instrumental, effectively creating a better data gathering tool. During the round table discussion, a participant called Brillembourg’s game a means to make big data ‘warm’ again, meaning the addition of an emotional component. Brillembourg expressed scalability as a key factor: there is not one size that fits all but instead, by making big data warm, his game can create a localized census of desires. Hopeful for the future is Brillembourg’s conviction that with these kind of games architects and game designers can cooperate more closely by relying on data gathering techniques but also visualization and sensorial means to make the city more livable.

Conclusion – Games for Cities

The conference on Games for Cities confirmed, contextualized, and complicated the findings of the earlier games for cities events. Speculative design seems to be a prevalent aspect in many of the games, often relying on scenario prompts and visualizations. The specificity of the play setting can vary from very location dependent to basically ubiquitous. Simultaneously the particular focus of the game can also vary from player provisions to a tool to tackle a problem. Striking is that despite these possible differences, agonic elements are often left out, preferring cooperation over competition. Ludic elements are often outnumbered by free form play but ironically the rules that set up play sometimes take a long time to explain, making the break-out sessions a bit short at times.

What these analyses have shown is that games for cities are a complex amalgam of urban planning, game design, architectural, and governmental issues. The current analytical tools have to be updated and combined in order to heed Gordon’s warning of pointless game use and Pedercini’s critique of singular Simcity ideas. The entertaining values of games doesn’t have to be ignored, as Madrazo showed, for games for cities to be useful but simultaneously a more tool use, like that of Brillembourg, requires a different approach to understand. The games for cities events have suggested two variables that can help in streamlining the debates but these are just two, informed from a game studies focus (mostly). To fully explore how to fit games for cities to urban issues requires multiple metrics to test these games. Nevertheless, games for cities have awoken as a means for urban planning, trying to tame the social complex system that never sleeps.

About Games for Cities

City-Gaming holds great potential in addressing 21st century issues and the Games for Cities project, an initiative by PLAY THE CITY, has set out to build an integrated community, developing a common language, and supporting newcomers. The Mobile City, the Lectorate of Play & Civic Media at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, and the Media and Culture Studies department at Utrecht University have partnered in this project, in which researchers and designers explore the role of gaming for complex urban issues.

Sources

Caillois, Roger. 2001. Man, Play, and Games. Translated by Meyer Barash. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Costikyan, Greg. 2013. Uncertainty in Games. Playful Thinking Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

De Lange, Michiel. 2009. ‘The Mobile City Project and Urban Gaming’. Second Nature 1 (2): 161–169.

Flanagan, Mary, and Helen Fay Nissenbaum. 2014. Values at Play in Digital Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Fullerton, Tracy. 2014. Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Gordon, Eric, and Stephen Walter. 2016a. ‘Meaningful Inefficiencies: Resisting the Logic of Technological Efficiency in the Design of Civic Systems’. In Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, edited by Eric Gordon and Paul Mihailidis, 243–66. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

———. 2016b. ‘The Good User: Tech-Mediated Citizenship in Modern American Cities’. In Companion to American Urbanism, 656. Routledge International Handbooks. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hughes, Linda. 1983. ‘Beyond the Rules of the Game: Why are Rooie Rules Nice?’ In The World of Play: Proceedings of the 7th Annual Meeting of the Association for the Anthropological Study of Play, edited by Frank E. Manning. West Point, NY: Leisure Point.

Juul, Jesper. 2013. The Art of Failure: An Essay on the Pain of Playing Video Games. Playful Thinking Series. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Lange, Michiel de. 2015. ‘The Playful City: Using Play and Games to Foster Citizen Participation’. In Social Technologies and Collective Intelligence, 426–34. Vilnius: Mykolas Romeris University.

Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. 2010. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Playful Thinking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

———. 2016. ‘Play and the City’. In Playin’ the City: Artistic and Scientific Approaches to Playful Urban Arts, edited by Judith Ackermann, Andreas Rauscher, and Daniel Stein, 25–40. NAVIGATIONEN Zeitschrift Für Medien- Und Kulturwissenschaften. Siegen: Universität Siegen.

Stenros, Jaakko, and Annika Wærn. 2011. ‘Games as Activity: Correcting the Digital Fallacy’. In Videogame Studies: Concepts, Cultures and Communication, edited by Monica Evans, 11–22. Critical Issues. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press.

Suits, Bernard. 1978. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Ontario: Broadview Press.