Last week we joined the Smart City world congress in Barcelona, a three-day event bringing together representatives of city governments, technology companies and academia with a common interest in the ways Smart Cities change the world.

As the biggest organisation in the field of Smart Cities, the event was largely dominated by representatives of major technology corporations like IBM, Cisco, Schneider etc. and local governments officials who try to employ smart city tools for their cities. In this framework there were two very clear directions of most presentations around one main theme. The first one focuses on offering efficient services to citizens/consumers. The second tries to actively engage citizens in the process of ‘city-making’.

The first direction is to offer more efficient services to citizens by empowering them to participate in processes laid out by their municipality. Technology companies seem to understand that cities will not hand over the control of all their infrastructure to just one company and they all now try to propose platforms that will enable the integration of city services provided by different parties and enhance the communication between municipal departments. A good example of this is Digital Delta, developed by IBM to bring under one platform big data related to water and flood management in the Netherlands that now are fragmented and come from different sources, in order to make the flood management in the Delta works more efficient and increase safety.

Most of the presentations confirm our assumption that the discourse around Smart City developments are very much technology driven and focus on efficiency, expecting citizens to act as consumers of apps that will provide the necessary input to local governments in order to act faster and perform better.

An inspiring exception in this direction was the presentation of Frank Kresin from the Waag Society, who presented an alternative direction: He supported the view that cities should not view their citizens as consumers but as partners and include them in Public – Private – People Partnerships. In many cases, people do not expect their governments to provide the framework for them to participate; they take matters into their own hands. Governments should refrain from constantly providing the framework; sometimes they should just provide the tools for people to develop their own solutions.

In the session on Citizen Engagement and Participation we met Dan Parham, founder and CEO of Neighborland, an exemplary case of a tool that allows multidirectional interaction among users themselves and users and governments or private parties. Parham described Neighborland as “a tool for planners” explaining that as cities run out of space, governments cannot buy “buy-in”, they really have to ask their citizens over more and more issues. Even though Neighborland is primarily a survey tool, it also encourages people to come together in action, which lead to the realisation of more than 100 projects over the last 3 years.

What was even more interesting was Parham’s view on the way these projects work and what he defined as the need for a “benevolent dictator” that follows closely and curates the process. His argument is that every successful open source or collaborative project ultimately has a strong well-intentioned leader behind it. Kickstarter carefully selects the projects that are eligible to be presented on their platform, Wikipedia has Jimmy Wales even Linus Torvalds closely follows the Linux development.

Another presentation touching upon appropriating urban spaces was made by Patricia di Monte, Town planning and Social Architecture professor at the ETSA San Jorge University of Zaragoza. She talked about the project “Esto no es un solar”, an employment project transforming 28 vacant plots in the city of Zaragoza in temporary public spaces. The main problem, common to many similar projects, is that the maintenance of these spaces is not secured forcing them to fall in decay sooner than later. So even though these programs are successful in engaging people in intervening in their neighbourhoods, they do not assign the responsibility to keep these spaces active and well maintained. As an elected official of the Municipality of Barcelona mentioned, including the people in decision making is highly desirable but in a representative democracy the responsibility ultimately falls on the back of the elected representatives, so they should be allowed to have the final word.

Also very interesting was the plenary session on the ‘Co-City: Collaboration, Entrepreneurship and Creativity’ starting with Anthony Townsend, research director of the Institute for the Future, explaining that smart cities create new exclusions because they centralise the management of cities. He observed that all the smart city platforms developed by big corporations are very orderly and they don’t include poor people. They simply forget to recognise that the majority of urban dwellers are poor and their numbers are growing exponentially. He consequently talked about ICT for Development for the global south and the urban poor and recognised three main directions, a pro-poor development when money is given without any support, para-poor innovation when skills and knowledge is transferred and per-poor innovation when designers use tools from the developed world to develop their own tools.

In the same line argued also Peter Madden, CEO of the Future Cities Catapult in London, saying that the smart city agenda oversimplifies urban problems when it should be embracing complexity and allow for systemic innovation to take place. Secondly we should accept that it is impossible for anyone to tackle city issues alone and we should be innovating collaboratively to tackle urban complexity. Finally, he noticed the successful thinking of user-centred designers because they are able to understand users’ needs and include them in the design process, an attitude that we should employ also in citymaking, start with the people and move on across scales.

Abha Joshi-Ghani from the World Bank stressed one more time that urbanisation is the defining phenomenon of our century, an observation shared by many presenters during the three days and this calls for the democratisation of urban development. She also noted three tools to achieve that, starting with what the Hackable Metropolis project also advocates, the handling of local resources under a commons management. Secondly, there is a need for participatory budgeting and a new vision on how the cities will physically look like on the level or urban planning. In this framework, design thinking can offer added value, as designers tend to think ahead and bypass existing problems.

Some interesting questions at the end lead the discussion to the “smartness” of cities in the developing world. This gave the opportunity to Joshi-Ghani to remind us that “smartness” is technology enabled but not technology driven and many cities in the developing world have highly efficient management processes that either are completely not based on technology or use very basic media. On the other hand, the assumption that the poor cannot pay is a myth, as the urban poor are usually paying more for basic services, (eg. for access to water) while all subsidies are directed to middle and upper classes. This comment stirred the discussion to the informal economies and the emergence of informal practices in the affluent world such as carpooling, airbnb and other sharing economies. It is obvious that they constitute a flourishing entrepreneurship because they are not regulated and cities do loose taxation income from these economies but at the same time, they offer a good service so it might even be best to let them be. They are hardly scalable anyway and there is a limited amount of issues that they can address. I could not help noticing a bit of arrogance in this view, as these economies are perceived as side effects of a connected world that can be left unregulated as long as they don’t address any critical issues.

The keynote speech of Richard Florida was all about creativity leading the way out of the crisis. Using known examples, Florida explained that we do not face an economic crisis alone but a crisis of our growth model. As this is not the first time in history we are facing such a condition he draw on several examples to suggest that passing from crisis to recovery requires the time of a generation and the emergence of a new growth model. In his view the crisis of the 1930’s, what he called “the most innovative decade in the 20th century”, was caused by the failure to identify a new growth model to accompany the changing conditions. While the industrialisation achieved an increase of the productivity, the growth model continued to be based on the exploitation of natural resources and raw material, till the system reached its limits. We are now facing the same problem: the passing from a trading economy to a service economy to a knowledge economy that is information intense and technology enabled requires the adoption of a new growth model that has yet to be defined. And here he locates the role of creativity, which is a typically urban phenomenon, stemming out of the balance between collaboration and competition in dense urban environments. “The factory is not any more the spatial field of the class struggle, it is the city as a whole”. Zoned cities do not provide the diversity necessary for creativity to develop. There is a need for dense, vibrant environments and the most successful cities already have found the ideal density. So we should avoid sprawling horizontally as well as vertically as they both eliminate serendipity but we should invest in mega-regions, clusters of cities that work together as the existing examples, the Randstad included, have proved very successful. In addition to making better use of our resources by connecting our cities we should also allow for greater social mobility, by providing opportunities to people to access services that become increasingly elitist, like education and healthcare.

The same approach of the necessity of a paradigm shift was also in the heart of the keynote by Amory B. Lovins, “Reinventing Fire” who said that fire is what made us human and fuel was what made us modern. As we keep overpopulating the world and urbanising we need a new fire to keep the globe going. Using a phrase attributed to Eisenhower “If you cannot solve a problem, you should enlarge it” Lovins tried to tackle two problems by enlarging their context and bringing them together. On one hand we have the increased need for energy consumed by our means of transportation and on the other the need for production of electricity. He argues that by adopting renewable energy for electricity production and turning our cars and planes into electricity we would be able to stop our dependency on fossil fuels, create a healthy environment and generate an economy that is larger and sounder than the one we are now operating in.

The Amsterdam Hackable Metropolis was presented in the last session of the conference among a panel with very interesting initiatives, among which Martin Brynskov, Associate Professor at Aarhus University presenting the “Scandinavian Third Way” and Cecilia Tham, Director of Makers of Barcelona that put in perspective the necessity of proactive citizen participation in the smart city discourse, as it is demonstrated by the growing makers movement and the emergence of communities of people who are willing to spend time and resources in making their own products, slowly leading to a new understanding of production and consumption.

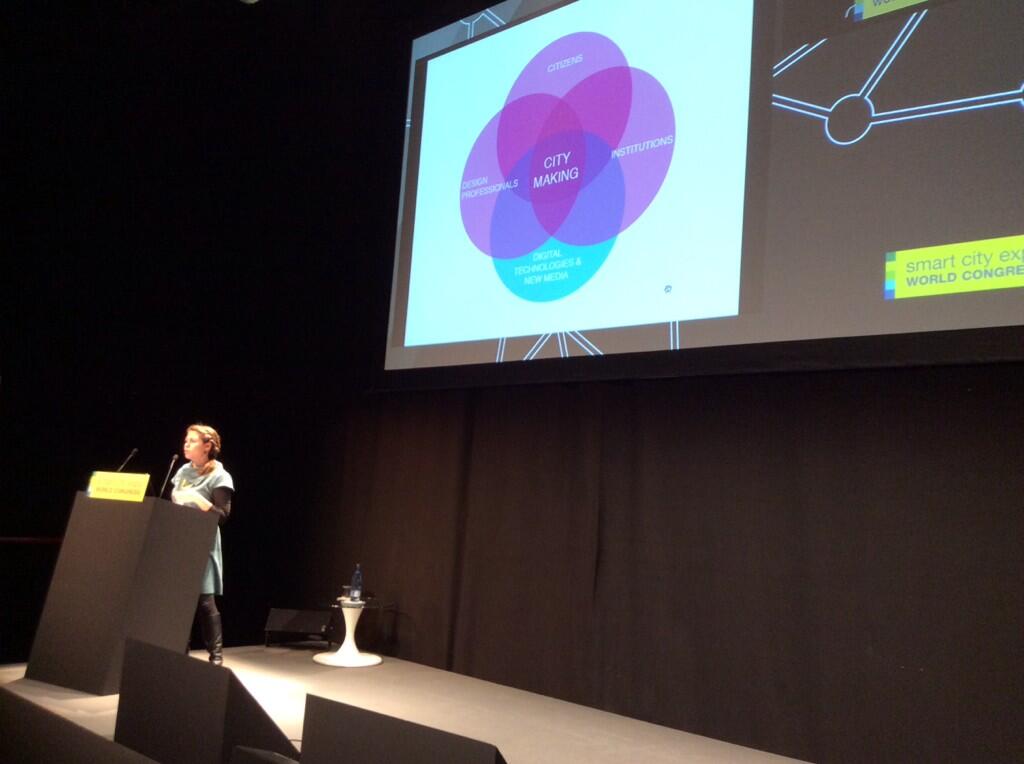

Amsterdam Hackable Metropolis is a research project initiated by The Mobile City, The University of Amsterdam and One Architecture and funded by Circa. As an embedded researcher, in the next 12 months, Cristina Ampatzidou will investigate the affordances of new media technologies for ‘city making’ and the changing roles of both professional designers, policy makers as well as citizens in that process.