A while ago our study ‘Ownership in the Hybrid City’ was published. The study, written in collaboration with Virtueel Platform, informs the upcoming event Social Cities of Tomorrow (14 − 17 Feb 2012). At this moment the study is being translated into English.

In the study we explore how digital media can strengthen ‘ownership’, that is, citizen engagement with collective urban issues and the capacity to act on them. The notion of ownership then is about inclusiveness, access and agency rather than exclusive proprietorship. Collective urban issues can have a global scope, like sustainability and social equity, or be locally specific, like shrinking cities and empty spaces. They are commons questions that involve multiple stakeholders, frequently with conflicting interests, and with divergent short and long term interests. The question therefore is: how can digital media be used to promote durable changes in citizen involvement, beyond being mere technological fixes?

The research started by compiling a longlist of cases. The list includes both international and Dutch examples. From the list several themes emerged. The themes share an underlying formative principle for stimulating or organizing ownership. In a series of two posts these are presented with examples. Note that many websites are in Dutch only.

4. Story-telling: a sense of place

Narratives are important mediators of personal and collective identities. People engage with their environment and with others when they recount and share stories and memories. With digital media normally hidden stories can be made public. The nature of storytelling itself changes too. Quite a lot of Netherlands examples exist.

Dutch examples

– Onder Anderen – http://www.onder-anderen.nl. ‘Among Others’ is a digital archive on an interactive map composed of the memories of people who lived in the Professorenbuurt, a neighborhood in Delft between 2007-2009.

– Geheugen van Oost – http://www.geheugenvanoost.nl. One of the first neighborhood website that allowed people to share stories and memories of living in Amsterdam-east. A project by Amsterdam Museum, Mediamatic and Dynamo, in collaboration with Buurtonline.

– Care-Taker – http://www.care-taker.nl. A history of the Amsterdam neighborhood Indische Buurt told by a Care-Taker who temporarily went to live in the neighborhood, helped people with small affairs, and reported about it on his weblog. By Dennis Kaspori and Jeanne van Heeswijk.

– Boven Tafel – http://boventafel.nl. ‘Above the table’ is an art walk based on the memories of inhabitants of Het Franse Gat, a neighborhood in Veenendaal.

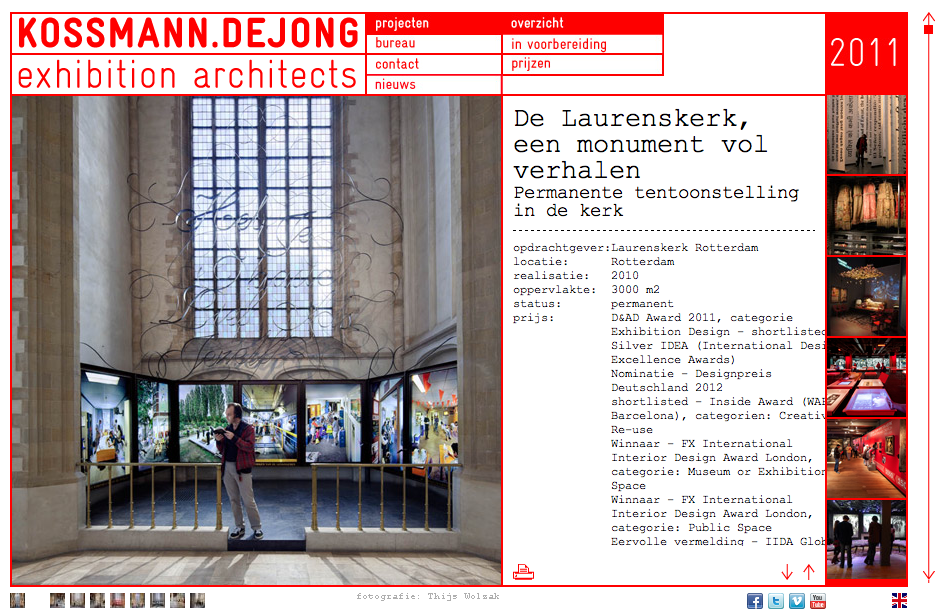

– Laurenskerk, a monument full of stories – http://www.kossmanndejong.nl/projects/view/98. Multimedia project by Kossman.DeJong in the Laurens church in Rotterdam, to make stories visible in architectural space.

– Amsterdam Realtime – realtime.waag.org. A project by Esther Polak and Waag Society. Different Amsterdammers were equipped with a GPS device and mobile data connection, which sent location info to a central server in realtime. In the exposition space a map slowly emerged out of the physical movements of the participants. They in turn reflected on their own mobility patterns, thus narrating and sharing their personal experiences of city life.

– Amsterdam Realtime – realtime.waag.org. A project by Esther Polak and Waag Society. Different Amsterdammers were equipped with a GPS device and mobile data connection, which sent location info to a central server in realtime. In the exposition space a map slowly emerged out of the physical movements of the participants. They in turn reflected on their own mobility patterns, thus narrating and sharing their personal experiences of city life.

5. Meeting in public space

Gatherings and interventions in the urban domain aim to tease out people onto the streets, connect to strangers and experience one’s environment anew. This may happen by using urban screens, media installations, urban play and games, flash-mobs organized with social media, or otherwise. Although some of these interventions center around specific issues they often are apparently pointless or seemingly silly in a Situationist tradition in order to open up room for spontaneity and avoid specifying in advance how people should behave and interact. In their yearly trendwatch our friends at The Pop-Up City note the rise of serendipity apps. Further, cities all over the world have seen so-called “pop-up” events (pop-up cafés, pop-up clubs, pop-up shops), often organized with a collaborative DIY attitude with the aid of social media. Their unexpected appearance and temporariness underline the transient nature of urban places. Yet the question is how durable these interventions remain after they disappear, and whether they aren’t catering to a disposable mentality towards novel urban services (‘swarm intelligence’ may easily become a locust plague when people rapidly graze a new resource to depletion and then turn to the next newest thing in town). Other projects aimed at meeting in public space are longer-lasting, for example neighborhood urban farming projects that use new media to organize and monitor affairs, and tap into the implicit knowledge of resident citizens.

International examples

– Flashmobs worldwide – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flashmob.

– Fallen Fruit – http://www.fallenfruit.org. People map and share ripe overhanging fruit trees in LA neighborhoods (municipal law allows picking outside private fences). This can be a way to meet with residents.

– Foodprint Project – http://www.foodprintproject.com. A “collaborative exploration of food systems. Our goal is to bring together people with diverse backgrounds and expertise to start a conversation about using food as a design tool to make our cities more resilient, sustainable and healthy”.

– Subtlemob – http://productofcircumstance.com. Project by Duncan Speakman that lets people undergo a cinematographic experience on the streets through a soundtrack. See also the complete portfolio of his projects at http://productofcircumstance.com/portfolio/.

– Subtlemob – http://productofcircumstance.com. Project by Duncan Speakman that lets people undergo a cinematographic experience on the streets through a soundtrack. See also the complete portfolio of his projects at http://productofcircumstance.com/portfolio/.

– Projects by urban design studio Civic Center – http://civiccenter.cc. Often low-tech and playful interventions that spur meetings.

– Tate Trumps mobile game – http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/information/tatetrumps.shtm.

– Pavement to Parks – http://sfpavementtoparks.sfplanning.org. San Francisco’s “Pavement to Parks” projects seek to temporarily reclaim unused swathes and quickly and inexpensively turn them into new public plazas and parks.

– TranquiliCity http://www.tranquilicityapp.com – One of the many serendipity apps.

Dutch examples

– WIMBY – http://www.wimby.nl. Welcome in my backyard is a project from 2007 by Crimson Architectural Historians and Felix Rottenberg in the Rotterdam neighborhood Hoogvliet. Aim was to elevate the large-scale restructuring of the neighborhood through various interventions together with inhabitants.

– Go for IT! – http://www.go-for-it-game.nl and http://go-for-it-rotterdam.nl/. This project by The Patching Zone is an urban game for and by inhabitants of Feijenoord, a neighborhood in Rotterdam. Pavement tiles were equipped with LEDs and sensors, which enabled playful interactions between people.

– Koppelkiek – http://whatsthehubbub.nl/projects/koppelkiek/. Social photo game developed by Kars Alfrink for the problem area Hoograven in the city of Utrecht. Designing simple social assignments made people come together in spontaneous ways.

– .dotwalk – http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/dot-walk/. This psycho-geographic project by Wilfied Houjebek applies a very simple computer algorithm as a prescription for urban walks in an attempt to stimulate serendipity and encounter.

– Dropstuff – http://www.dropstuff.nl. Interactive art wall using a huge screen. It connects the digital world to urban public space, and allows people to control the screen through their mobile devices.

– Storylines – http://www.sndrv.nl/nff. “”Storylines” turns a citycentre into a 3D surround film-set of a ‘movie’ happening in augmented reality. Using the smartphone app “Layar” a world of scenes and storylines can be explored. Dialogues are still hanging in the air, as the geo-located textual remains of movie scenes which occured throughout the city.”

– Storylines – http://www.sndrv.nl/nff. “”Storylines” turns a citycentre into a 3D surround film-set of a ‘movie’ happening in augmented reality. Using the smartphone app “Layar” a world of scenes and storylines can be explored. Dialogues are still hanging in the air, as the geo-located textual remains of movie scenes which occured throughout the city.”

– Moodwall – http://www.illuminate.nl/outdoor-media/projects/16/moodwall-bijlmerdreef-amsterdam-zuidoost.asp. A 24 meter long media facade aims to improve people’s sense of security in a pedestrian tunnel in the south-east of Amsterdam, by displaying various interactive projections. Designed by Jasper Klinkhamer (Studio Klink) and Remco Wilcke (CUBE architects).

– Play Real – http://www.creatieve-innovatie.nl/page/1208/nl. PlayReal is an online/offline augmented reality game, that uses a global social network, coupled with real world assignments. PlayReal hands its players (10 – 16 year olds) tools and skills to engage in local problem solving of global environmental and societal issues. Initiative: Ahead of the Game: Claudia Rodiguez Ortiz, Alex de Jong and Minne Belger. Development partner: The Beach / Diana Krabbendam

– The Cook, the Farmer, His Wife and Their Neighbour – http://kkvb-cfwn.blogspot.com. A participatory project by the Slovene artist and architect Marjetica Potrč (b. 1953) and Wilde Westen, a group of young designers, architects and cultural producers, combines visual art and social architecture to redefine the village green. Community vegetable gardens become a tool by which the residents of Amsterdam Nieuw West reclaim ownership of their neighborhood at a time when demolition and redevelopment are causing many to feel uprooted.

– Nu Hier – www.nuhier.org. A project by Ester van de Wiel. “NU HIER is an initiative that links vacant sites with users from the neighbourhood, schools, clubs, corporations, and associations. Their cooperation and combined entrepreneurship is the engine behind what in this case is a project on the periphery of the centre of Rotterdam”. Using principles from e-culture, the project taps into local ‘Pro-Am’ knowledge http://nuhier.mmmmx.net/article/971/diy-do-it-yourself/.

6. Peer-to-peer economy: social currencies and collaborative consumption

A main concern in any attempt to ‘govern the commons’ is how people can be persuaded to prioritize long term collective benefits over short term individual profit. Reputation management is a social enforcement mechanism to counter the ‘free rider’ problem and strengthen trust. Social currencies can keep track of, and disclose individual contributions to the collective good. In the present so-called ‘economy of free’ this can be a way to monetize contributions. New currencies can stimulate stronger relationships between consumers and local entrepreneurs. While alternative currencies predate the widespread use of digital media, these media make keeping bookkeeping and trust management much easier. Bridging the gap between production and consumption, crowdfunding provides investors with a sense of ownership of the product they support and forges connections with other investors and a more direct relation with the producer. Not surprisingly, crowdfunding initiatives frequently display multi-tiered and publicly visible donations lists. Collaborative consumption attempts to move away from a strictly market view of social interactions as economic transactions. It is a hybrid model for consuming resources that reconciles private ownership with collective use by creating semi- common-pool resources (CPRs) out of privately owned property. In this peer-to-peer economy, digital media technologies enable the realtime sharing of scarce resources, whether parking spaces, cars, plots of land, tools and machinery, energy, food and meals, couches, and so on. These developments thus redefine ownership from possession to access, or from proprietorship to usage rights (much in the same way as the Turntoo concept developed by architect Thomas Rau aims to save scarce natural resources by promoting performance-based consumption instead of property-based consumption).

International examples:

– ParkatmyHouse – http://www.parkatmyhouse.com/uk/. ParkatmyHouse is the world’s largest online parking marketplace created to connect home and business owners who would like to earn money from renting their space with drivers in need of a convenient, safe and cost-effective place to park.

– Landshare – http://www.landshare.net. Landshare brings together people who have land to share with those who need land for cultivating food via the website and a location-based mobile app.

– Landshare – http://www.landshare.net. Landshare brings together people who have land to share with those who need land for cultivating food via the website and a location-based mobile app.

– Funding revolution – http://www.forumforthefuture.org/project/funding-revolution/overview. A guide to establishing and running revolving funds for community energy generation and renewal and carbon saving, based on a different ownership model.

– Hey, Neighbor! – http://heyneighbor.com. Share tools or help a hand in your neighborhood.

Dutch examples:

– Bijlmer Euro – http://www.bijlmereuro.net. Project by Christian Nold to develop a social currency that expresses and visualizes the relations between inhabitants and local businesses. Nold also helped develop the Lewes Pound and the Brixton Pound.

– I Make Rotterdam http://crowdfunding.imakerotterdam.nl. Crowdfunding intiative for a temporary pedestrian arial bridge at Hofplein in the centre of Rotterdam. An intiative of ZUS architects in collaboration with Hofbogen B.V., within the framework of the 5th International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR). “Crowdfunding allows the bridge to be financed in an alternative way, namely directly by the public. This means that construction can start decades before it is planned.The necessary improvement in the quality of the area is therefore no longer fully dependent on policy plans and real estate developments”.

– WeGo – http://www.wego.nu/en/. A community car sharing platform.

– WeGo – http://www.wego.nu/en/. A community car sharing platform.

Conclusion

Digital media are used to address a wide variety of collective issues at the city level. In part 1 we have seen that sensing data can be opened up as new resources. We have looked at new ways of organizing and managing collective action by making urban issues public through sensing and visualizations, and even more actively in DIY urbanism. In part 2 we have looked at ways of strengthening people’s sense of place through story-telling and how unexpected events, playful activities or appealing to their latent knowledge can be ways to get people together and meet. And we looked at new economic models that redefine ownership, and turn from a transactional view of social relations to a reciprocal view in which mutualism prevails.

Despite their differences, the above examples have one thing in common. They share a fundamentally relational view of city life, in which individual components – places, people, organisations, infrastructures, technologies; information and matter – are deeply intertwined. Simple ‘technological fixes’ will not do to help solve urban issues that are by nature complex. In most examples it is not the technology that is central but the collaborative spirit from e-culture that is ported to urban questions. That implies new roles for citizens. Citizenship becomes less about individual rights and obligations vis-a-vis state institutions, but more about generating awareness, trust and responsibility needed for collective governance. Only then can our cities truly become more social.