(This article was published a few days ago on Engaging Cities, as a guest contribution)

Social Cities: how to engage citizens with digital media

Michiel de Lange – The Mobile City

The increasing growth and complexity of cities raises the question how we can use digital media technologies and principles from online culture to design livable and lively cities. How can digital media aid citizens to engage with their environment, with fellow urbanites, and with issues at stake in their cities? Most mobile and location-based apps are about personalized consumption and sharing preferences with an in-group of like-minded people. Can we use digital technologies to help solve collective problems in the city too?

Some collective issues have a global span, like social equity, environmental sustainability, and water, food, and energy provisioning. Others, like shrinking cities, aging populations, or empty buildings, are locally specific. Many cities also face issues like the perceived loss of publicness, safety, social cohesion, and the gap between citizens and government. Typically, complex urban issues like these are not exclusively ‘owned’ by a single party. They are commons issues that involve multiple stakeholders who often have incompatible interests, and therefore they need collective forms of governance.

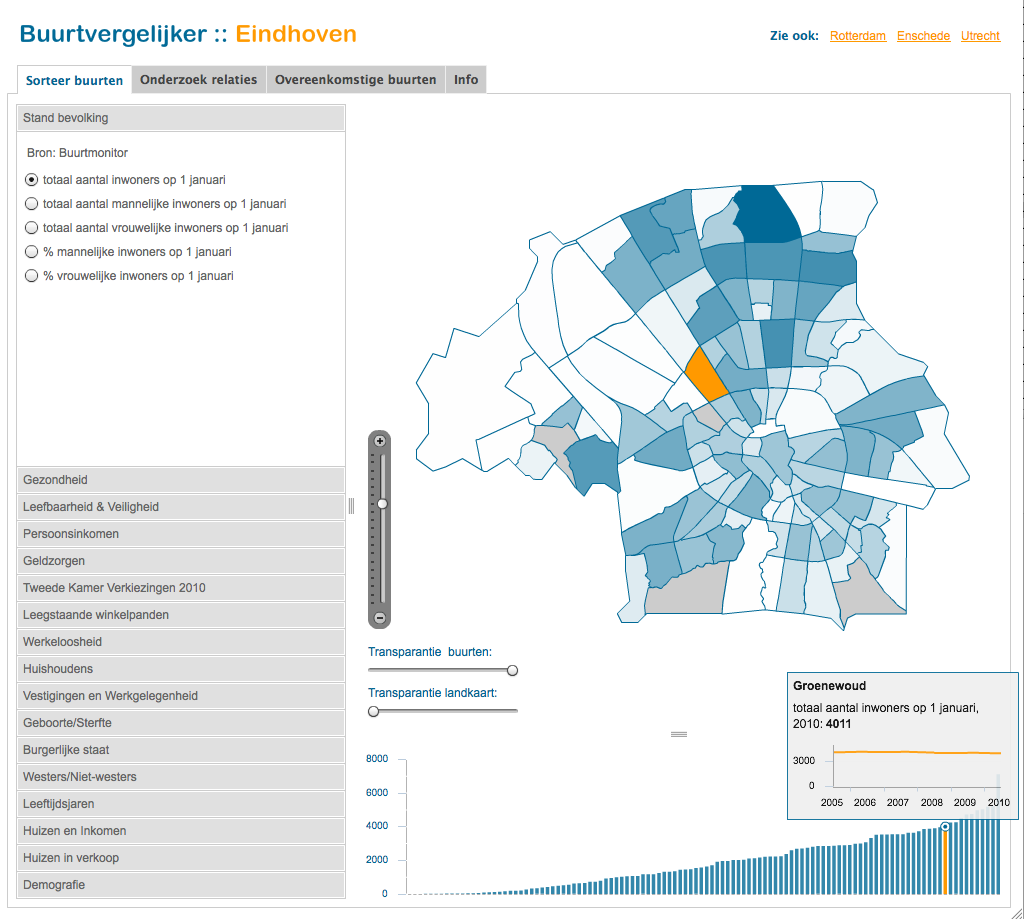

Cities collect huge amounts of data. Until recently these data often disappeared in the vaults of (public) institutions. These data could become new resources that provide valuable knowledge about urban processes and citizen behavior – a data-commons. In the Netherlands cities like Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Eindhoven experiment with open data initiatives and collaborate with developers to see what interesting apps and services they can build.

Using municipal open data, the website Buurtvergelijker (‘neighborhood comparer’) allows people to compare statistical information from different neighborhoods.

In what is known as reality-mining these new resources provide insights in what is happening. Information can be used to provide people with consumer recommendations based on shared patterns (Citysense), but it can also inform design programs better tailored to citizen’s needs (Twitterhouse). In the data-commons scarcity takes on another meaning. The challenge is to design interventions where individual use does not deplete the commons but instead adds value to the whole. For example, the more people use location-based services like traffic reports, and feed information back into the system, the more accurate the service becomes.

For decades policy makers, institutions and architects have tried to persuade people to actively participate in shaping their cities. Often these remain top-down trajectories. The bottom-up extreme is a community model rooted in proximity, shared interests and similar lifestyles. Yet this denies the nature of cities as places of heterogeneity and the fact that many urbanites shiver at the thought of village-like parochialism. With digital media new networked publics can be activated, beyond top-down or bottom-up but peer-to-peer and distributed. An illustration is Verbeterdebuurt (the Dutch take on Fixmystreet). This is a mobile and web app that allows citizens to report problems in their neighborhood, but also to suggest improvements and vote on each other’s ideas, and therefore assemble others around collective issues.

In the small Dutch town of Hoorn, young people successfully used the platform Verbeterdebuurt.nl to get a skate ramp built in their neighborhood (photo: Stijn van Balen).

Digital media thus allow citizens to co-design their own environment. An interesting project in Amsterdam is Face Your World by artist Jeanne van Heeswijk and architect Dennis Kaspori. Young people and other people living in this neighborhood collaborated in designing a city park using a 3D simulation environment. With this crowdsourced plan they managed to persuade the local government to abandon the initial plans for the park and execute theirs instead.

In Face Your World people co-created a neighborhood park by using a digital environment in which they could upload their own images and ideas to debate amongst each other (photo: Dennis Kaspori).

Cities worldwide (like Amsterdam) are embracing smart city policies in close collaboration with tech companies and academia to optimize urban processes. These policies are technologically driven and despite claims to the contrary tend to ignore an active role of citizens. If we truly want engaging cities, it is urgent we start exploring how we can make our cities more social rather than more high-tech.

—

From February 14 − 17 2012 the international conference and workshop Social Cities of Tomorrow takes place in Amsterdam, NL, organized by The Mobile City, Virtueel Platform and ARCAM.