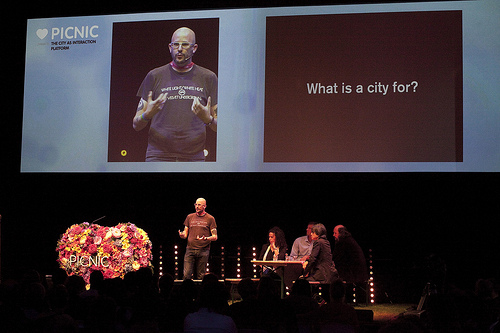

At Picnic I attended an interesting session called The City as an Interaction Platform that took this theme as its point of departure:

Cities have always been about providing frameworks of services to improve the quality of life for residents and businesses. How will social networks, mobile devices, reactive environments, and cloud-based data services transform the experiences of living in cities in the coming years? What new municipal infrastructure will evolve to meet the needs of citizens looking for the type of real time information and configurability they have come to expect from Internet applications?

|

| http://www.flickr.com/photos/crossmediaweek/ / CC BY-SA 2.0 |

It was interesting to see three completely different takes on these issues. First Ben Cerveny of Vurb sketched an optimistic view of the ‘cloud city’ – a future scenario in which citizens could get easy access to urban informatics and use those as the foundation for a blossoming civil society. Greg Skibiski of Sense Networks provided another optimist vision – be it based on a different paradigm – in which urban computing is used as the base of offering ever more personalized information and localization services for urbanites. Adam Greenfield however argued that when taken up in a certain way, the rise of urban computing might do urban culture more harm than good. What is at stake, he argued, are some of the essences of urban culture.

Ben Cerveny / Vurb

Cerveny’s argument is centered on the premise that the city has always been an information system: it is a place where people come together, interact and exchange information, culture and goods. This process lies at the heart of both urban society as well as the market economy and leads to both (cultural) innovation as well as the continuation of urban society. This is not a process that is somewhere up in the air: over the centuries it has led to certain institutionalized practices. For instance in the seventeenth century Amsterdam was the birth place of the Broadsheet newspaper – an institution that started as an information tool on stock prices and shipping information (a ‘dashboard device’ in contemporary business terms) for business men and grew into an important pillar of the public sphere in democratic societies.

Similarly one can think of urban society as an ‘operating system’: specific practices and power relations have over the centuries been institutionalized in the laws that regulate how people are to interact and who has what rights in the city. They form the kernel of a civil society, so to speak.

At the same time, in the 20th Century cities had grown into sites of spectacle and consumption, epitomized by the skylines of New York – or even better: Las Vegas. The beginning of the 21st century however has shown a whole new dynamic: the informatization of urban culture, related to a number of developments:

- The rise of sensor networks that sense and track objects, people, institutional output and other sources (climate, energy use, etc.)

- The availability of this data in real time aggregated data flows

- The rise of actuation devices that can operate on either individual or aggregated data.

- Participatory affordances of digital media and its peer-to-peer distribution model that allow citizens to not just consume data streams, but produce and redistribute them themselves as well.

These combined phenomena lead to the rise of what Cerveny has coined ‘cloud city’: ‘The geometry of the city is no longer just the skyline. It now also includes the graph of its social networks.’ This new situation offers a range of new opportunities for civil society. (VURB’s website lists some of these in more detail).

- Responsive Environments – the environment starts to know what is going on. “What are the mechanisms by which these services are provisioned by the tasks that citizens utilize them for?”

- Urban Systems Literacy & Civic Information Systems – can data visualization of complex interactions in the city lead citizens to get a better grasp of what is happening around them (Like the newspaper did in the 17th century)?

- Collaborative Redevelopment– multiparticipant social models (analogue to for instance World of Warcraft) that allows people to interact socially on common goals.

Taken together, this leads to the formation of a new Urban Operating System, one that is not just written in the code of law but also in software code. This means that Urban Interface Policy becomes an important aspect:

In the smart city, what is written as programmatic software ‘code’ can easily become defacto ‘law’ as it imposes permissioning schemes and identity regimes on it’s participants. So far, the internet, and the open source software that powers much of it, has remained remarkably adaptable to the ideals of democratic and egalitarian societies. Every infrastructural advance, however, goes through a watershed moment where the governing design principles of the technology itself begin to influence the types of societal experiences they might produce.

Greg Skibiski / Sensenetworks.com

Greg Skibiski’s company Sense Networks is one of those institutions involved in bringing about the cloud city. The tag line of his company is ‘Indexing the real world using location data for predictive analytics.’

Whereas Cerveny conceptualized the city as the locus for both a civic society and a market place (of both commerce and culture), Sense Networks approaches the city from an individual point of view: how can we make everything the city has to offer more relevant for its users? (see also my review on the Handbook of research on Urban Informatics for this conceptual difference. A similar discussion on ‘what is a city for’ also came up in the Picnic Session on augmented reality. )

The way it is trying to do this, is by analyzing large sets of location data provided by operators of mobile phone networks. Every mobile phone user constantly beams his location to the network so that the network can find him or her when someone else tries to call. They have developped an appliction – Citysense – that takes all this (anonimized) data, aggregates it and visualizes it. City Sense thus provides a map of San Francisco that shows real time traffic flows of people in the city:

The way it is trying to do this, is by analyzing large sets of location data provided by operators of mobile phone networks. Every mobile phone user constantly beams his location to the network so that the network can find him or her when someone else tries to call. They have developped an appliction – Citysense – that takes all this (anonimized) data, aggregates it and visualizes it. City Sense thus provides a map of San Francisco that shows real time traffic flows of people in the city:

Citysense shows the overall activity level of the city, top activity hotspots, and places with unexpectedly high activity, all in real-time. Then it links to Yelp and Google to show what venues are operating at those locations.

What they plan to do next is analyzing this data in ways similar to how Google analyzes the web: how many people that are now at location A have been at location B before? And how many of those will move on to location C rather than location D? Citysense uses this information to distill the behavior of different ‘urban tribes’, or in the words of Skibiski to compose a ‘lifestyle matrix’: people with similar spatial patterns and preferences for nightlife venues, restaurants or other urban amenities. This matrix can – this will be the next step that hasn’t been implemented yet – be used as the engine for recommendations.

So: while you move around the city with your mobile phone in your pocket, your phone company is drawing up a lifestyle profile of you, based on your geographical movement. This profile can then be used to get recommendations for restaurants, shops, people, etc – in an Amazon.com style. They call this a shift from ‘searching’ to ‘sensing’:

The application learns about where each user likes to spend time – and it processes the movements of other users with similar patterns. In its next release, Citysense will not only answer “where is everyone right now” but “where is everyone like me right now.” Four friends at dinner discussing where to go next will see four different live maps of hotspots and unexpected activity. Even if they’re having dinner in a city they’ve never visited before.

- 360p MP4

- Flash

Adam Greenfield

Adam Greenfield took a critical stance towards developments in urban computing. In a similar fashion to Ben Cerveny he conceptualized the city as an ‘interface’ – a system that continuously brings different worlds together. Or more precise: ‘The city is creating the maximum of interfaces in a minimum area’, the city is a complex system that brings together different people with different identities, goals, cultural backgrounds etc and provides them the interface to interact with others in order to achieve their personal goals.

While they do that, on an aggregate level other processes emerge. To illustrate that, Greenfield referred to Jane Jacobs who found that safety on city streets emerges because a number of different people (shop keepers, visitors, playing children, neighborhood inhabitants on their way to work or doing groceries) find themselves together in those streets – basically to mind their own business. Yet at the same time, the presence of all those people creates what Jacobs has coined ‘eyes on the street’: enough people keeping an eye out to provide a sense of safety. While nobody has been ordered to act as a safe keeper of the street, its safety emerges from the many eyes on the street, brought together by the function of the street as a collection of interfaces for different social processes. This is also what theorists like Sennett argue: the city is an interface that brings us in contact with people who are not like us, and it is this interaction that makes the city interesting and leads to an enrichment of our personalities as well as to social processes that foster urban culture as a whole.

Now, the problem with urban computing or networked informatics is that it shapes the process of meeting and encounter in a different way: ‘Spaces become addressable and query-able. It allows me to give instructions like: Please find me a Vietnamese Restaurant within 10 blocks that has a liquor license and a good sanitation record.’ This is a conceptual shift that Greenfield has theorized as a shift from browsing to searching. However, the search is always based on personal preferences – it is usually based on ‘affinity’ and ‘like’. Greenfield fears that this threatens the function of the city as an interface that brings differences together. Of course it is pleasant and comfortable. But while browsing might lead to confrontations with the unexpected, searching runs the risk of never finding anything truly different. (See also the interview we had with Adam Greenfield last year at Picnic)

The shift from browsing to searching also brings up another issue and that is that of the cultivation of local knowledge in relation to (sub)cultural capital. Part of the essence of being an urbanite, Greenfield finds, lies in the fact that one has accumulated a body of local knowledge of the best restaurants, hidden record shops, club nights etc. It takes years and years of browsing the city to build such a body of knowledge, that then can become part of one’s identity. Yet what happens if all this knowledge suddenly becomes available by a simple search query? Of course it would be nice to instantly find the secret spots when we visit an unknown city. But doesn’t it take something away from the process of browsing and discovery that is at the base of urban culture? (See also my post on Local knowledge and subcultural capital)

13 responses to “Picnic 09 Report 2: The City as an Interaction Platform”

[…] Read full story Leave a Reply […]

Fascinating conversation, but somehow just that. Somehow we have to move beyond urban philosophy to expound real theories about real phenomena and how they are experiened by people in the city, not in an hypothesis. I can’t criticize any of these presentations for lack of creativity, insight, and good logic — but the overall impression of too many prognostications, at least to this reader, is that we create much ado by way of pronouncements but don’t change anything or alter any trajectories by doing so. Cities today are alternately wonderful and awful experiences. In the digital world, what concretely can be done to increase the woner and decrease the awful? And who will do it? Why, with what, and how?

Martijn,

Impressive series of possibilities. Spatial data is increasingly critical. I work for independent innovation analysts, 2thinknow.

We created an Innovation Cities Framework to assist cities to create change – to improve economic and social performance. What we have is ‘implementation’ framework for cities.

In many cases a cloud/mobility is a part of that infrastructure.

There’s more info on the website: http://www.innovation-cities.com – we’ve just released this week the Innovation Cities Analysis Report outlining how to achieve change.

Keep innovating,

Sam

[…] Leggi tutto l’articolo Scrivi un commento […]

[…] It strikes me that today when people talk about the city as a platform, they are often making some variant of an analogy to computing. See, for example, “The City as Interaction Platform“. […]

[…] Picnic 09 Report 2: The City as an Interaction Platform (conference report) […]

[…] Picnic 09 Report 2: The City as an Interaction Platform (conference report) […]

[…] If you would like to read more on some of these issues, see also an earlier post on The City as an Interaction Platform, as well as my contribution to the Sentient City book, that builds upon the issue brought about by […]

[…] Urban designLa città come piattaforma interattiva […]

[…] Urban design La città come piattaforma interattiva […]

[…] the wildly diverse (and divergent) category of superorganisms we call cities: as platform, sites of cloud computing or heightened ambition, scaled behaviors, or structural racism. Perhaps most remarkable is the […]

[…] Or what to think of services that based on their analysis of your urban trajectories assign you to a lifestyle profile that from then on is used to recommend places to go, activities to undertake and people to meet. Would you eventually subscribe to such a continuous lifestyle address made to you by your mobile phone? (see also my article on Sensenetworks) […]

[…] It strikes me that today when people talk about the city as a platform, they are often making some variant of an analogy to computing. See, for example, “The City as Interaction Platform." […]